Advanced command-line¶

Apart from simple problems, the command-line is able to solve more tricky cases such as cases when

- one of the images has its spectrum cut (e.g. when different objectives were used),

- you want to apply interpolation (you have nice images and desire sub-pixel precision),

- one (or more) of rotation, scaling, or translation is known (so you want to help the process by narrowing possible values down) and

- the subject’s field of view is a (small) subset of the template’s (which is a huge obstacle when not taken care of in any way).

Frequency spectrum filtering¶

If you want to even images spectra, you want to use low-pass filters. This happens for example if you acquire photos of sample under a microscope using objective lenses with different numerical aperture. The fact that spectra don’t match in high frequencies may confuse the method.

On the contrary, if you have some low-frequency noise (such as working with inverted images), you need a high-pass filter.

--lowpass,--highpassThese two concern filtration of images prior to the registration. There can be multiple reasons why to filter images:

- One of them is filtered already due to conditions beyond your control, so by filtering them again just brings the other one on the par with the first one. As a side note, filtering in this case should make little to no difference.

- A part of spectrum contains noise which you want to remove.

- You want to filter out low frequencies since they are of no good when registering images anyway.

The filtering works like this:

The domain of the spectrum is a set of spatial frequencies. Each spatial frequency in an image is a vector with a \(x\) and \(y\) components. We norm the frequencies by stating that the highest value of a compnent is 1. Next, define the value of spatial frequency as the (euclidean) length of the normed vector. Therefore the spatial frequencies of greatest values (\(\sqrt 2\)) are (1, 1), (1, -1) etc.

An argument to a

--lowpassor--highpassoption is a tuple composed of numbers between 0 and 1. Those relate to the value of spatial frequencies it affects. For example, passing--lowpass 0.2,0.3means that spatial frequencies with value ranging from 0 to 0.2 will pass and those with value higher than 0.4 won’t. Spatial frequencies with values in-between will be progressively attenuated.Therefore, the filter value \(f(x)\) based on spatial frequency value \(x\) is

\[\begin{split}f(x) = \left\{\begin{array}{ll} 1 & : x \leq 0.2\\ -10\, x + 3 & : 0.2 < x \leq 0.3 \\ 0 & : 0.3 < x \end{array} \right.\end{split}\]where the middle transition term is a simplified form of \((0.3 - x) / (0.3 - 0.2)\).

Note

A continuous high-pass filtration is already applied to the image. The filter is \((1 - \cos[\pi \; x / 2])^2\)

You can also filte the phase correlation process itself. During the registration, some false positives may appear. This may occur for example if the image pattern is not sampled very densely (i.e. close or even below the Nyquist frequency), ripples may appear near edges in the image.

These ripples basically interfere with the algorithm and the phase correlation filtration may overcome this problem. If you apply the following filter, only the convincing peaks will prevail.

--filter-pcorr- The value you supply to this filter is radius of minimum filter applied to the cross power spectrum. Typically 2–5 will accomplish the goal. Higher values are not recommended, but see for yourself.

Interpolation¶

You can try to go for sub-pixel precision if you request resampling of the input prior to the registration. Resampling can be regarded as an interpolation method that is the only correct one in the case when the data are sampled correctly. As opposed to well-known 2D interpolation methods such as bilinear or bicubic, resampling uses the \(sinc(x) = sin(x) / x\) function, but it is usually implemented by taking a discrete Fourier transform of the input, padding the spectrum with zeros and then performing an inverse transform. If you try it, results are not so great:

[user@linuxbox examples]$ ird sample1.png sample3.png --resample 3 --iter 4 --print-result

scale: 1.2492 +-0.001619

angle: -30.0507 +-0.0375

shift (x, y): 104.977, 218.134 +-0.08333

success: 0.2343

However, resampling can result in artifacts near the image edges. This is a known phenomenon that occurs when you have an unbounded signal (i.e. signal that goes beyond the field of view) and you manipulate its spectrum. Extending the image and applying a mild low-pass filter can improve things considerably.

The first operation removes the edge artifact problem by making the opposing edges the same and making the image seamless.

This removes spurious spatial frequencies that appear as a + pattern in the image’s power spectrum.

The second one then ensures that the power spectrum is mostly smooth after the zero-pading, which is also good.

[user@linuxbox examples]$ ird sample1.png sample3.png --resample 3 --iter 4 --lowpass 0.9,1.1 --extend 10 --print-result

scale: 1.249 +-0.001557

angle: -30.0446 +-0.035714

shift (x, y): 104.953, 218.093 +-0.08333

success: 0.2207

As we can see, both the scale and angle were determined extremely precisely. So, a warning for those who skip the ordinary text:

--resample- The option accepts a (float) number specifying the resampling coefficient, so passing 2.0 means that the images will be resampled so its dimension become twice as big.

Warning

The --resample option offers the potential of sub-pixel resolution.

However, when using it, be sure to start off with (let’s say) --extend 10 and --lowpass 0.9,1.1 to exploit it.

Then, experiment with the settings until the results look best.

Using constraints¶

imreg_dft allows you to specify a constraint on any transformation.

It works the same way for all values.

You can specify the expected value and the uncertainity by specifying a mean (\(\mu\)) and standard deviation (\(\sigma\)) of the variable.

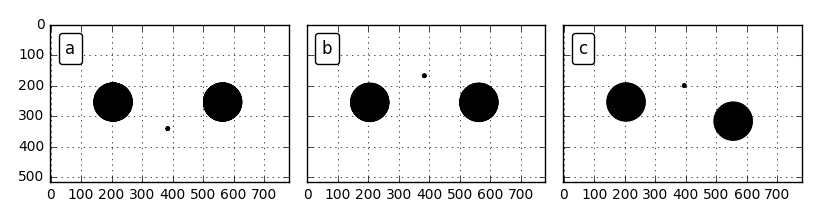

Values is proportionally reduced in the phase correlation phase of the algorithm. Here is what happens if we force a wrong angle:

When the template and subject are the same, the algorithm would have no problems with the registration. If we force a certain angle by specifying a value with a low \(\sigma\), the result is obeyed. However, the algorithm is actually quite puzzled and it would fail if we didn’t specify the scale constraint.

[user@linuxbox examples]$ cd constraints

[user@linuxbox constraints]$ ird tricky.png tricky.png --angle 170,1 --scale 1,0.05 --print-result

scale: 0.9934 +-0.001803

angle: 169.836 +-0.057618

shift (x, y): -17.3161, 23.2186 +-0.25

success: 0.2317

When we place a less restrictive constraint, a locally optimal registration different from the mean (180° vs 170°) is found:

The template and the subject at the same time (a), registered with --angle 170,10 (b) and registered with --angle 170,1 (c).

You can use (separately or all at once) options --angle, --scale, --tx and --ty.

Notice that since the translation comes after scale change and rotation, it doesn’t make much sense to use either --tx or --ty without having strong control over --angle and --scale.

You can either:

Ignore the options — the default are null constraints.

Specify a null constraint explicitly by writing the delimiting comma not followed by anything (i.e.

--angle -30,).Pass the mean argument but omit the stdev part, in which case it is assumed zero (i.e.

--angle -30is the same as--angle -30,0). Zero standard deviation is directive — the angle value that is closest to -30 will be picked.Pass both parts of the argument — mean and stdev, i.e.

--angle -30,1, in which case angles below -33 and above -27 are virtually ruled out.Note

The Python argument parsing may not like argument value

-30,2because-is the single-letter argument prefix and-30,2is not a number (unlike-30.2). On unix-like systems, you may circumvent this by writing--angle ' -30,2'. Now, the argument value begins by space (and not by the dash) which doesn’t make any trouble further down the road.

Large templates¶

imreg_dft works well on images that show the same object that is contained within the field of view with an uniform background.

However, the method fails when the fields of view don’t match and are in subset-superset relationship.

Normally, the image will be “extended”, but that may not work.

Therefore, if the subject is the smaller of the two, i.e. template encompasses it, you can use the --tile argument.

Then, the template will be internally subdivided into tiles (of similar size to the subject’s size) and individual tiles will be matched against the subject and the tile that matches the best will determine the transformation.

The --show option will show matching over the best fitting tile and you can use the --output option to save the registered subject (that is enlarged to the shape of the template).

Result¶

The following result demonstrates usage of ird under hard conditions.

.. There are two images, the template is taken from confocal microscope (a), the subject is a phase acquired using a digital holographic microscope [4].

Pretty much everything that could go wrong indeed went:

- Spectrums were not matching (the template is sharper than the subject).

- The template obviously shows a wider area than the subject.

- The images actually differ in many aspects.

Well, at least the scale and angle are somehow known, so it is possible to use constraints in a mild way.

The question is — will it register?

And the answer obviously is — yes, if you use right options.

One of the right commands is

[user@linuxbox examples]$ cd tiling

[user@linuxbox tiling]$ ird big.png small.png --tile --print-result

scale: 0.51837 +-0.004024

angle: 40.5952 +-0.16854

shift (x, y): 156.397, 136.526 +-0.25

success: 0.6728

The template (a), subject (b) and registered subject (c).

Try for yourself with the --show argument and be impressed!

| [4] | Coherence-controlled holographic microscope. Pavel Kolman and Radim Chmelík, Opt. Express 18, 21990-22003 (2010) http://www.opticsinfobase.org/vjbo/abstract.cfm?URI=oe-18-21-21990 |