Developer’s Guide¶

The base of the class hierarchy is Abstract class that does nothing except providing the Abstract.__call__() interface with ‘message’ and ‘context’ parameters:

def __call__(self, *message, **context):

raise NotImplementedError('Method not implemented')

The communication between objects should use only this method for message exchange:

a = AbstractImpl()

a('ultimate question', mode=42)

Message Handling¶

Handler class is a base class for condition-event based message processing. It contains the list of condition-event pairs and uses the Handler.handle() method to find the best condition for the message in a certain context and return the result of the event’s call for that condition. The condition and event could be objects, values, or user functions.

To add a new condition-event pair, the Handler class provides an Handler.on() method:

def on(self, condition, event, *tags)

For example:

h = Handler()

h.on('event', lambda: True)

print h('event')

> True

print h('tneve')

> False

An optional Handler.tags parameter binds the condition to the state of the handler and will be described later.

When called, the ‘on’ method converts condition and event parameters to Condition and Event wrapper classes and puts the pair into the Handler event list.

Condition Class¶

Condition is processed based on its type – a string, regular expression, user function, etc. This is done by the Condition.setup() method of the Condition class, which sets up the correct Condition.check() function to analyze the message and compare it with the condition value. One may ask why in dynamic typed language, there is a need to worry about types. The reason is very simple: speed. It is too expensive to call non-applicable checks and/or use try blocks each time when looking for the best condition – using a type-specific comparison gives a very significant performance boost.

The default declaration of the user function to be used as a condition has the same form as the Abstract.__call__() method. When checking, it receives data from the Handler.handle() method. For example:

user_condition = lambda *message, **context: return message and message[0] == "hi"

The result of the condition check is one or two values: check rank and check result. Check rank is a relevance indicator for the condition and the check result is actually the outcome of the check. For example, the check rank of “a+” regular expression for the message “aa” is 2 and the check result is “aa”.

| Check result | Meaning |

| One numeric value | Check rank, Check result will be equal to check rank |

| Two values: numeric and arbitrary | Check rank is first and Check result is second |

| One boolean value | Rank = 0 if True, -1 if False, Check result = value |

Logical checks have 0 rank by default. Check result is useful for the event and will be included in the context during the event’s call. For example, if the condition returns True, the event context will contain {'rank': 0, 'condition': True}.

If the condition did not work, it returns (-1, False) or Condition.NO_CHECK value.

The condition has an ignore_case option, which is False by default. It affects only string conditions.

Let’s see how different types of conditions work, always for message[0].

| Condition type | Rank and result | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Function | Should return the check rank or check rank with the check result | lambda *m, **c: (1,"ok")

any message[0]

rank = 1,

check result = “ok”

|

| Regular expression - match | Length of the expression matched and match result | ‘a+’

message[0] = “aa”

rank = 2

check result = “aa”

|

| Regular expression - search | Same as above, but using the search method | “b+”

message[0] = “agabb”

rank = 5

check result = “bb”

|

| String – match | Length of the string if message[0] starts from the string and string itself as a result | “stop”

message[0] = “stop”

rank = 4

check result = “stop”

|

| String – search | Same as above, but using the find method of string class | “run”

message[0] = “now run”

rank = 7

check result = “run”

|

| Boolean value | 0, True if message[0] equals value | False

message[0] = False

rank = 0

check result = False

|

| List | Highest rank for each list item check | [“1”, “11”]

message[0] = “11”

rank = 2

check result = “11”

|

| Other value | 0 or value length if applicable, message[0] as the result | 8

message[0] = 8

rank = 0

check result = 8

|

For example:

h = Handler()

def show_me(*m, **c):

print c

return

h.on(re.compile('a+'), show_me)

h('aaa')

> {'sender': <gt.core.Handler object at xxx>, 'condition': 'aaa', 'rank': 3, 'event': <function show_me at xxx>}

Here you see the context content for the event. It contains ‘h’ object as a sender of the message, passed condition, its rank, and show_me as a selected event. More information on events is below.

There is one more very important benefit from the wrapper classes called context mapping.

Context mapping¶

If the condition function or event function always uses declarations like:

def handler1(*message, **context)

the most frequent operation within such functions will be:

if context.get('param', 'default'):

...

To save the developer’s time, Graph-talk implements its so-called “context mapping” feature. If you need to analyze only certain values from the context, you just need to specify their names in the condition or event parameter list. So, the previous example will look like this:

def handler1 (param='default')

If the context contains ‘param’ value, it will be used when calling the user function. The table below describes possible context mapping cases.

| Function declaration | Call result |

| handler (*message) | Only the message parameter will be filled |

| handler (**context) | Only the context parameter will be filled |

| handler () | No parameters |

| handler (a, b=1) | Corresponding parameters will be pulled from the context, default will be used if there is no such key |

| handler (*message, **context) | Default call, both parameters will be filled |

| non-callable value | The value will be returned |

Usually, condition functions only accept the message to check for message[0] contents. For example, the show_me function in the previous example could be declared as:

def show_me(**c)

The class that implements the context mapping is called Access and is used as a base class for Condition and Event classes. Access, in turn, is a child of the Abstract class.

Event Class¶

Event functions can declare any arguments or do not declare them at all. If the condition was satisfied, the condition check result will be included in the context of the event call:

h = Handler()

h.on("continue", do_continue)

def do_continue(**context):

...

Event context will contain the following parameters with corresponding values:

- Handler.RANK = len(“continue”), 8 in this case

- Handler.CONDITION = “continue”

- Handler.EVENT = do_continue

- Handler.SENDER = h

A special feature of Event class is Event.pre and Event.post properties, which can contain other events to be called before or after user function. If the pre- or post-event will return a non-empty result, this result will be used instead of the one returned by user function. For example:

c = Condition(re.compile('a+'))

e = Event(show_me)

h.on_access(c, e) # No need to wrap

e.pre = 1

print (h('a'))

> 1

Pre and post properties accept any functions, which will be wrapped in the Event class and executed via the Event.run() method. If you want to use the Event instance as a pre/post-event, write it directly to Event.pre_event or Event.post_event field.

Note that if the post-event was specified, the Event.RESULT context value for its call will contain the value returned by the user event function.

Handling step-by-step¶

- Define conditions and events for the handler instance using the arguments needed for checking the condition and running the event.

- Add the condition and event via the Handler.on() method or via Handler.on_access() if you want to add Condition and Event instances.

- Handler will try each condition against the incoming message and context to find the one with the highest rank. If several conditions return the same value, the first one will be used.

- The event of the winning condition will be called, and its result will be returned from the handle method as a tuple (event_result, condition_rank, event_found).

- If there is no condition found, the handle will return Handler.NO_HANDLE. There is a way to handle all unknown messages: the Handler class provides the Handler.unknown_event property, which will be called if no condition worked. Its result will be returned from the handle method.

- By default, the __call__ method of Handler returns only the event_result value, no condition rank and so on.

- If the Handler.ANSWER context value was set to Handler.RANK, __call__ would return (event_result, rank) tuple: a("ultimate question", mode=42, answer=Handler.RANK). This will be used by Selective notions.

Some examples (the code from the previous example was used) are the following:

h.handle(['aa'], {})

> (1, 2, 1)

h.handle([], {})

> (False, -1, None)

Tags¶

The Handler class provides a simple ‘state-like’ condition filter to avoid unnecessary checks. You can specify a set of tags for the condition in the Handler.on() method to reflect for which state it is applicable:

h.on("move", do_move, "has_fuel", "has_direction")

The Handler instance has the set of current tags, which reflect its current state and Handler.update() method. Update does a very simple thing: it keeps in the condition-event pair list used by handle method only the conditions which tag set is a subset of the handler tag set.

First, update calls the Handler.update_tags() method. It returns the set of tags describing the current situation. If it is different from the existing set, update filters the list of active conditions and events.

If tags are {“has_fuel”, “maps_loading”}, the “move” message will not be considered at all. If tags are {“has_fuel”, “has_direction”, “doors_closed”} – the “move” condition-event pair will be active.

For example:

class UpdateTest(Handler):

def __init__(self):

super(UpdateTest, self).__init__()

self.fixed_tags = set()

def update_tags(self):

return self.fixed_tags

u = UpdateTest()

u.on('move', Event(True), 'has_fuel', 'has_direction')

print u('move')

> False

u.fixed_tags = {'has_fuel', 'maps_loading'}

u.update()

print u('move')

> False

u.fixed_tags = {'has_fuel', 'has_direction', 'doors_closed'}

u.update()

print u('move')

> True

The Handler.update() method should be executed manually in appropriate cases. Use the Handler.tags field to access the current tags.

Building and Walking the Graphs¶

The graph is a set of Notions and Relations. It has a root notion whose name is also the name of the graph. Both notions and relations have the same parent class: Element. The parent class of the Element class is the Handler.

Graph Element¶

As mentioned above, the process asks the element what to do next. That means sending the corresponding message to it. For the “forward” direction, the message is “next” (defined as Process.NEXT); for the backward direction, the messages are “previous” (defined as Process.PREVIOUS), “break” (defined as ParsingProcess.BREAK), “continue” (defined as ParsingProcess.CONTINUE), and “error” (defined as ParsingProcess.ERROR).

The Element class uses the Handler’s features to respond to process messages. It has two convenience methods: Element.on_forward() and Element.on_backward() to assign customized events to reply to the process.

As an example, ActionNotion uses the ‘on_forward’ event to specify the user function to be triggered when the process passes the notion.

Each Element belongs to a certain graph, which is set by the Element.owner property. When the owner changes, Element sends the “set_owner” message to the old and new owners so they can update their internal references.

Walking the Graph¶

Different elements respond differently to the Process.NEXT process message.

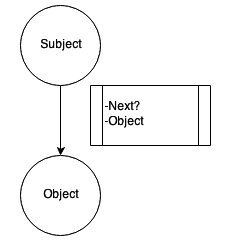

Basic Notion is a leaf of the tree (“Object” in the figure below), so it does not return the next element. ActionNotion could trigger a user function to do something when reaching this notion.

Basic Relation (an arrow in the figure above) does not reply to process messages – it just connects two elements together (subject and object). NextRelation replies with the Relation.object to the Process.NEXT message, thus providing a way to pass itself forward, from the top to the bottom of the graph. It also has the NextRelation.condition to be checked before replying. If the condition is specified and False, the relation will not be passable. ActionRelation is similar to ActionNotion – it triggers a user function when passed.

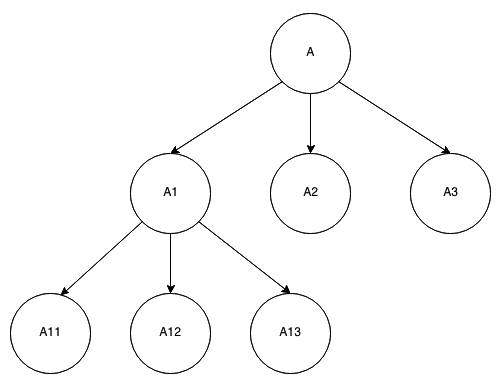

ComplexNotion consists of other notions and implies the presence of all of them. It returns not just one relation but the whole “to-pass list.” Some of those relations could lead to another complex notion. To support this, the process has a list of elements to visit, implemented as a queue.

For example, complex notion “A” contains “A1, A2, A3” notions; “A1” is a complex notion too and contains “A11, A12, A13” notions. The process receives [“A-A1”, “A-A2”, “A-A3”] list of relations from “A.” When process visits “A1” and pops the first element, it receives [“A1-A11”, “A1-A12”, “A1-A13”]. The “to-pass” list will look like this: [“A1-A11”, “A1-A12”, “A1-A13”, “A-A2”, “A-A3”]. The process always works with the head of the queue; it takes commands/elements from it and puts back the replies from the elements.

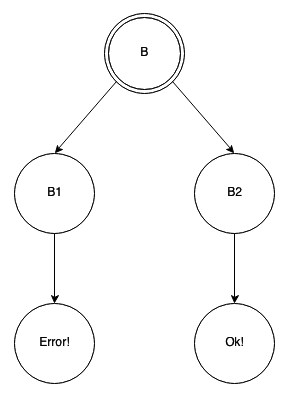

SelectiveNotion is a kind of complex notion that finds the best relation to pass in the current context. It checks all of its sub-relations for the highest relevance rank and returns the best one to the process. Here, the trick is that several relations could return the same rank.

For example, selective notion “B” contains “B1, B2” notions via NextRelations without conditions. That means both “B-B1” and “B-B2” will have the same rank equal to zero. The final decision of which case is good is yet to be revealed somewhere later. So, the process needs to try both relations. If the first one fails, we will need to revert all changes to the initial state when we’ve made the decision to try “B-B1” and “B-B2”. This is a general approach called lookahead. With lookahead, you try one case, and if it does not work, you try another one.

Lookahead and Error Handling¶

Each time the element makes a decision about how it should reply to the process, it considers only the message and the context. This is a very important assumption because if we ask the same thing in the same context, the result should be the same as well. Imagine that we took a wrong turn at the selective notion and several elements later found that we could not move further. What if the context had already changed? If we had had an original context state, we could have just returned to the initial point and could have tried another case (or cases)—pretty much like transactions work. This is how it works in Graph-talk, step by step:

- The selective notion finds that there is more than one relation to try.

- That means we need to keep the original context. This is done via a “push_context” (defined as StackingProcess.PUSH_CONTEXT) message to the process. The process creates a restore point for the future and puts it to the stack.

- Besides StackingProcess.PUSH_CONTEXT, selective notion returns the first case (first relation) to try and the reference to itself to talk again later.

- Process picks the first case and talks to it, moving forward while possible.

- If an error is encountered (some element returned an ParsingProcess.ERROR message), the process reverses its direction and starts to ask elements with not the Process.NEXT but the ParsingProcess.ERROR question. Elements stop to answer, and this question will finally go to the initial selective notion.

- If the case worked fine, the process would go to selective notion as well, but without an error.

- When selective notion is visited again with an error, it restores the context (via StackingProcess.POP_CONTEXT command) and tries another case, changing the direction of the process to forward again (step 2).

- If there was no error, selective notion just discards the stored context because it is not needed anymore (StackingProcess.FORGET_CONTEXT command).

Lookahead looks a bit similar to the exception handling. The only difference is that the process does not really go back – it just changes its message. It starts asking “error” to each element in its “to-pass” list, starting from the current one until some element will handle it. If there were several nested selective notions, they would pop the saved contexts from the stack one by one. If no case worked, the “error” message would go to the higher level, and the process finishes.

If an element keeps and changes its state out of the context, it means its state cannot and will not be reverted. There is a way to store the state conveniently within the context – it will be described later.

Context and State¶

The context could be used for information exchange between the elements. For example, an element may put there some data, which will be used by another element. To handle this, the following messages are used: “add_context” (defined as SharedProcess.ADD_CONTEXT), “update_context” (defined as SharedProcess.UPDATE_CONTEXT) and “delete_context” (defined as SharedProcess.DELETE_CONTEXT). For example, an ActionRelation may say to the process, “add_context”: {“warning”: “under_construction”}, and another ActionRelation could use it in the handler via context mapping:

def is_safe_road(warning):

return None if warning else self.object

If there is a need to roll back during lookahead, all the changes in the context done through these commands will be reverted – just as the undo operation works.

If the element needs to keep in the context some private information that should not be shared but be a part of the rollback, there is a pair of commands to do this: “set_state” (defined as StatefulProcess.SET_STATE) and “clear_state” (defined as StatefulProcess.CLEAR_STATE). First, one will set the specified value as a state for the current element. When this element is visited, its state will be sent to it as part of the context in the StatefulProcess.STATE value. No other element will see this state. If the state is not needed anymore, just clear it.

For example, the complete selective notion reply for lookahead looks like this, given that the “case” is the first relation to try, and “cases” is the list of all other relations with the same rank: [“push_context”, {“set_state”: {“cases”: cases}}, case, self].

The state will be sent as part of the context, so context mapping could be used to handle it as well. Note that if the state is a complex value like a dictionary, its content will not be reverted. Only the top-level value will be rolled back. An example of how the state works for loops is below.

Looping¶

Let’s say that some complex notion should appear exactly N times. This is what LoopRelation does. It repeats its object according to the condition specified. Here are the supported conditions:

- Integer N

- Ranges M, N (from M to N); M, ... (at least M and more); ..., N (0 to N).

- Wildcards: “*” (from 0 to an infinite number of times), ”?” (0 or 1 time), “+” (more than one time)

- User function

- TRUE_CONDITION (infinite loop)

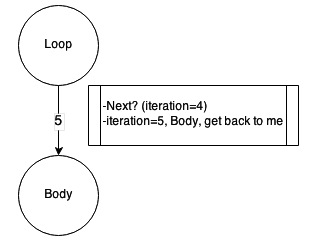

Loop uses both state and lookahead. In the simplest case, it says to the process, “set my state to the number of iteration, then take the object, and come back to me after all.” When the process comes back to the loop again (note – it still is a forward direction), it checks the iteration number; if it is within the bounds, it repeats the cycle with an iteration of + 1.

If there is a LoopRelation.is_flexible() (without an exact number of repetitions) condition used, like “*”, it works in a bit of a different manner. We do not know how many times the Object should appear, so the loop says, “push the context, then go to the object, and come back to me.” If there was no error – fine, at least one iteration worked. However, there may be more Objects, so we need to iterate again, now with a different context – the one we have now. The old context is discarded, and a new one is put to the stack. Reusing the transaction analogy, try several payments: if the first one works, update the balance, and try another one.

If an error occurs and conditions were satisfied, the loop restores the last-known good context and ends, changing the direction of the process to forward again. Otherwise, it clears the state and keeps the error propagating further.

Loops could handle ParsingProcess.CONTINUE and ParsingProcess.BREAK messages as most programming languages do. If the element says “break,” the process changes its question from “next” to “break” and keeps going until it finds someone who can handle it. First, the loop consumes it and does the appropriate handling, stopping the iterations and clearing the state. It also changes the direction to forward.

Building the Graphs¶

GraphBuilder is the class to construct graphs. It allows chained operations, so the building process looks like this:

builder = GraphBuilder('New Graph')

builder.next_rel().complex('initiate').next_rel().notion('remove breaks').back().back().next_rel().act('ignite', 1)

print Process()(builder.graph)

> 1

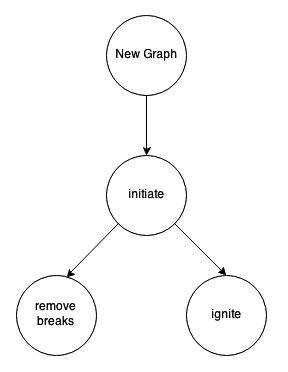

This is the graph:

The builder has used the GraphBuilder.current element to attach the result of the operation performed. The new builder will create an empty graph with the root notion under the specified name and use it as a current element. Adding the next relation will use the current notion element as a subject. Adding a new notion after the relation will attach it as an object to the current relation, and so on. Back operation will traverse the current element back depending on its type.

To access the graph itself, use the GraphBuilder.graph property. The graph allows searching for the notions by name and relations by object and subject.

For example, to find all the notions with names that start from “i” in the graph above use builder.graph.notions(re.compile('i+')). You can pass user function to the search as well.

For example:

print builder.graph.notions(re.compile('i*'))

> [<ComplexNotion("initiate", {"New Graph"})>, <ActionNotion("ignite", {"New Graph"})>]

To find all relations with the same subject, use builder.graph.relations({Relation.SUBJECT: subject_value}).

GraphBuilder allows setting the current element directly via the GraphBuilder.set_current() method to continue building from the certain place. Check its API description for other operations.

Processes¶

There are different kinds of processes; each has its own dialect.

The base class for all processes is called Process. It is a sub-class of Handler. Its Process.handle() method is designed to not only process one message but also continue the handling while the queue of replies from other elements is not empty. Process has the Process.current element to ask for directions and analyze the reply. For example, when the process says “next” to the relation, it replies with the Object value. The process sets the current to the Object returned and asks it what’s next and so on.

When the element replies with the list of elements, as complex notion does, they are processed one by one. The process has a queue of elements to go through and keeps working until the queue is not empty or the process faces a message it cannot recognize. When the handling is over, its result will be returned from the handle method, as Handler class does.

The element can reply not with just other elements to pass next, but with some commands. If the list of commands returned, they would be processed one by one as well. Basic process knows the following commands:

- Process.OK – finish handling, return “ok” as the result of the handling.

- Process.STOP – stop handling, return “stop.” It is possible to continue from the current element.

- True/None – if the element returns any of this, the process just continues the handling.

- False – if the element returns False, the process stops handling and returns False as well. It looks as though the element cannot process the question, so something is wrong here.

- Element – use the element as a current one. When the process meets an element in the message, it puts the new item to the queue to know which reply it currently analyzes.

- Process.NEW – start the new handling, clearing the process state.

Here is an example of the simple process:

process = Process()

n = Notion('N')

print process(n)

> True

The result is “True” because the basic notion will return None on the “next” question. As you see, the call to the process starts from the initial element to start handling and some context values. The process is a container for the context, so several processes can walk the same graph simultaneously.

If execute process() after it had stopped, the process will continue from the current element. Any context provided will just update the current one. To start from scratch, put the Process.NEW command first in the list, like process(Process.NEW, graph).

Sharing, Stacking and Stating¶

Basic process is a very simple thing that allows working in a pipeline manner walking the graph element-by-element, stopping at unknown messages, and continuing when needed.

SharedProcess is a child of Process that allows adding, updating, and deleting context parameters. The main interface of the Abstract - __call__(*message, **context) does not provide a way to change the context. This is good from the security standpoint, but sometimes, it is necessary to change the context in an explicit and controllable manner. The commands SharedProcess.ADD_CONTEXT and SharedProcess.UPDATE_CONTEXT accept the dictionary to merge with the current context, for example, {"add_context": {"type": "integer", "value": 8}}. The command SharedProcess.DELETE_CONTEXT accepts the name or names of parameters (as a list) to remove them from the context, for example, {“delete_context”: “mana”}.

StackingProcess is a child of SharedProcess and provides the way to “stack” the context states. This process has to provide a undo-style functionality to perform rollbacks of the context to saved the previous condition. This is done using putting of context change operations into the undo groups with information required for rollback.

For example, when the StackingProcess.PUSH_CONTEXT command comes, StackingProcess starts the new group of operations. Each operation contains undo commands, for example, “add parameter x” stored with “remove parameter x,” “update parameter y” stored with “previous value of the parameter y,” and “remove parameter z” stored with “add parameter z”. When undo is needed and the StackingProcess.POP_CONTEXT command comes, the group will be reverted as a single operation so the context will be restored.

Rollback does not include the internals of the context parameters because the overhead will be too big.

If the stored context state is not needed anymore, for example, when an error has not happened, StackingProcess.FORGET_CONTEXT removes the last stored undo group on the top of the stack. In this case, the context will remain changed.

StatefulProcess is a child of StackingProcess and supports two commands to provide the elements with the way to keep their state private. The first command is StatefulProcess.SET_STATE, and it accepts the dictionary to be set as a state, like {"set_state": {"iteration": 1}}. The second command is StatefulProcess.CLEAR_STATE. It has no parameters and just removes the state from the context.

SelectiveNotion and LoopRelation keep their state using this approach; first, to keep the list of cases for lookaheads and second, to count the iterations.

The state of the element is stored in the StackingProcess separately for each of the element. When the current element changes, the process removes its state from the context and adds the state of another element instead, so it is completely private.

The state-changing commands are included in the push and pop context operations.

Note that the Process.NEW command clears the stored contexts and the states.

Parsing the text¶

Parsing the text means analysing the character string according to the rules represented by the graph. So, some special kind of the process should be taken as an input and not only as a start element of the graph, but also as a text. The text will become a parameter of the context, so the elements will be able to consider the text content when making decisions about what the process has to do next.

The new type of the element that analyzes the text is called ParsingRelation. It is a subclass of the NextRelation and uses the condition not just to decide where the process should go but also to remove the processed part of the text.

The simplest example is skipping the white space. We check for the white space at the text’s beginning. The condition of ParsingRelation to handle this is a regular expression. The rank it returns in case of a positive result is used to cut off the fragment of the text of the equal length. The command to remove the start of the text is {"proceed": length} (defined as ParsingProcess.PROCEED).

After a successful parse, the text shrinks, and the process moves to the next element. What happens in other cases? ParsingRelation returns the “error” (defined as ParsingProcess.ERROR) message to the process, which starts to go in the backward direction, trying to recover from the error.

There are two options for ParsingRelation for more flexible parsing: The first one is ParsingRelation.optional, which means the “error” should not be produced, but the object will not be returned as well. It just returns None, and the process goes somewhere else.

Another one is ParsingRelation.check_only. In this case, ParsingRelation just checks the condition but does not consume the text:

builder.parse_rel(re.compile("/s+"), None, optional=True, check_only=True)

The object of the ParsingRelation could be a sub-graph for the processing of the certain feature or the action to create the element of the new graph that represents the structure of the parsed information (like in Brainfuck example).

Parsing Process¶

The process that knows how to work with the text is called ParsingProcess. ParsingProcess is a subclass of StatefulProcess. Other processes are focused on the graph walking, but this one is focused on the text, and ParsingProcess.TEXT is one of its context parameters. Therefore, the “text” will be included in all “next” queries to the elements.

ParsingProcess supports the “proceed” command to remove the start portion of the text. The fact that the text is a context parameter means it is a part of the rollback. So, its value will be restored to try another path in the graph in case of an error.

The “proceed” command changes not only the text parameter of the context but also two others: the ParsingProcess.PARSED_LENGTH parameter indicates the total length of the text parsed, and the ParsingProcess.LAST_PARSED parameter keeps the last portion of the processed text. An example of whitespace is ‘last_parsed’, which will keep the whitespace character.

Another command is “error,” which makes the process change its question and ask “error” instead of “next”. Two other commands have similar behaviors: “continue” and “break.” The process itself does not know anything about loops or error-handling stuff; it just stops processing the current message and changes the question it asks to the elements from the queue. If the direction should be set to forward, the “next” command is used.

Note that if the text parameter is not empty at the end of the parsing, the result of the process will be “false”.

A simple demo:

root = ComplexNotion('root')

process = ParsingProcess()

parsing = ParsingRelation(root, action, 'a')

print "%s, %s" % (process(root, text='a'), process.context.get(process.LAST_PARSED))

> True, a

Errors¶

The “error” command is not a user-friendly way to express the errors. Its goal is to change the way the process communicates with the graph elements. Such error does not always indicate a bad file or parsing problem. It recommends building a special path, which is selected in case of the error. ActionNotion or ActionRelation included in this path shall print or store the error information to present it later in a user-friendly format (the approach used in COOL example).

Another approach is to stop the parsing process and make the error message considering the context and current element. This works well in case there is no need to continue parsing if a problem appears (the approach used in Brainfuck example).

Summary¶

To parse the text with Graph-talk, the graph should represent the algorithm of recognition of logical concepts. In other words, this is a de-serialization of concepts from their text representation.

The process walks the graph querying the elements for directions basing on the context, where one of context parameters is the source text. Other parameters may include the state of the element or the process.

If several directions are eligible, it is possible to try them one by one to find a valid one. The context will be restored to the state when the decision to try the invalid case was made.

The result of the text parsing could be the list of tokens (lexing) or another graph that will contain the parsed concepts to be used on the next stage - syntax and semantics validation, interpretation, or code generation.

Debugging¶

It is tricky to debug the graph because it is challenging to find the right instance of a certain element type. For example, if you put the breakpoint into a method of relation, it will trigger for all relations. Of course, it is always possible to set the breakpoint inside the user function, but this will limit the debugging possibilities.

Graph-talk provides the utility class called ProcessDebugger in debug.py module. The most useful information when debugging the graph is to see the transcript of the communication between the process and graph elements. It is easily done with the following code:

p = Process()

d = ProcessDebugger(p, True)

cn = ComplexNotion('CN')

n1 = Notion('N1')

n2 = Notion('N2')

NextRelation(cn, n1)

NextRelation(cn, n2)

p(cn)

The log is:

To show the log, ProcessDebugger connects to post-event of query event of the process. It provides the result of the chat with the current element.

Another option is to reply to the process something at the certain element, for example, say “stop” when the process comes to the element. This is done using the reply_at method of the debugger that replies to the process with the specified value:

root = ComplexNotion('root')

n = ComplexNotion('n')

NextRelation(root, n)

d.reply_at(n, process.STOP)

print p(p.NEW, root)

> stop

For replying, the ProcessDebugger uses the post-event of pushing the reply of the element to the queue. This way, the debugger provides access to what’s replied and overwrites the reply with the specified answer value.

Export and Visualization¶

Visitor Process¶

VisitorProcess process walks through the graph and asks “visit” query to each element. Upon this query, an element returns other connected elements. Visitor process makes sure each element will be visited only once. When visiting a new element it calls VisitorProcess.visit_event event to check should the element be visited or not. Adding the custom event for this call allows exporting the graph structure or other similar processing.

Export Process¶

ExportProcess extends the VisitorProcess to implement the export framework.

The export uses “visitor” pattern to explore the graph structure. On each new element it calls ExportProcess.on_export() (connected to VisitorProcess.visit_event) to export the Process.current. Depending on its type the export process calls ExportProcess.export_notion(), ExportProcess.export_relation() or ExportProcess.export_graph(). Each of those methods returns the export string to be written into the output file or export buffer in ExportProcess.out. The export file is specified in ExportProcess.FILENAME context parameter.

To distinguish the elements while exporting, ExportProcess gives each of them unique ids. This is done by ExportProcess.get_element_id() method. Unique id consists of the abbreviation of the element type and the counter of such elements already processed.

ExportProcess.get_type_id() generates the type part of the id. For all elements except Graph, the type id will consist of the first capital letters of their class name. For example for ComplexNotion, the result is ‘cn’, for Notion the result is ‘n’. For a graph, the type id is ‘graph’.

Having the type id, ExportProcess.get_serial_id() adds to it the zero-based counter and generates the element id. For example, the first ActionRelation will have ‘an_0’ as an element id. Overwrite this method to change the ids generation policy.

The serial id is then cached internally by the get_element_id method with a key equal to the element, so the same element will always get the same id.

Note that the non-graph element, like function or other object do not get serial id. They get the name using ExportProcess.get_object_id() that returns the name of the function or string representation of the primitive.

DOT export¶

DOT is a plain text graph description language. It is a simple way of describing graphs that both humans and computer programs can use.

There is an experimental DotExport class that allows to see the picture of the graph. It generates the file that you can view in any DOT file viewer, for example with Graphviz.

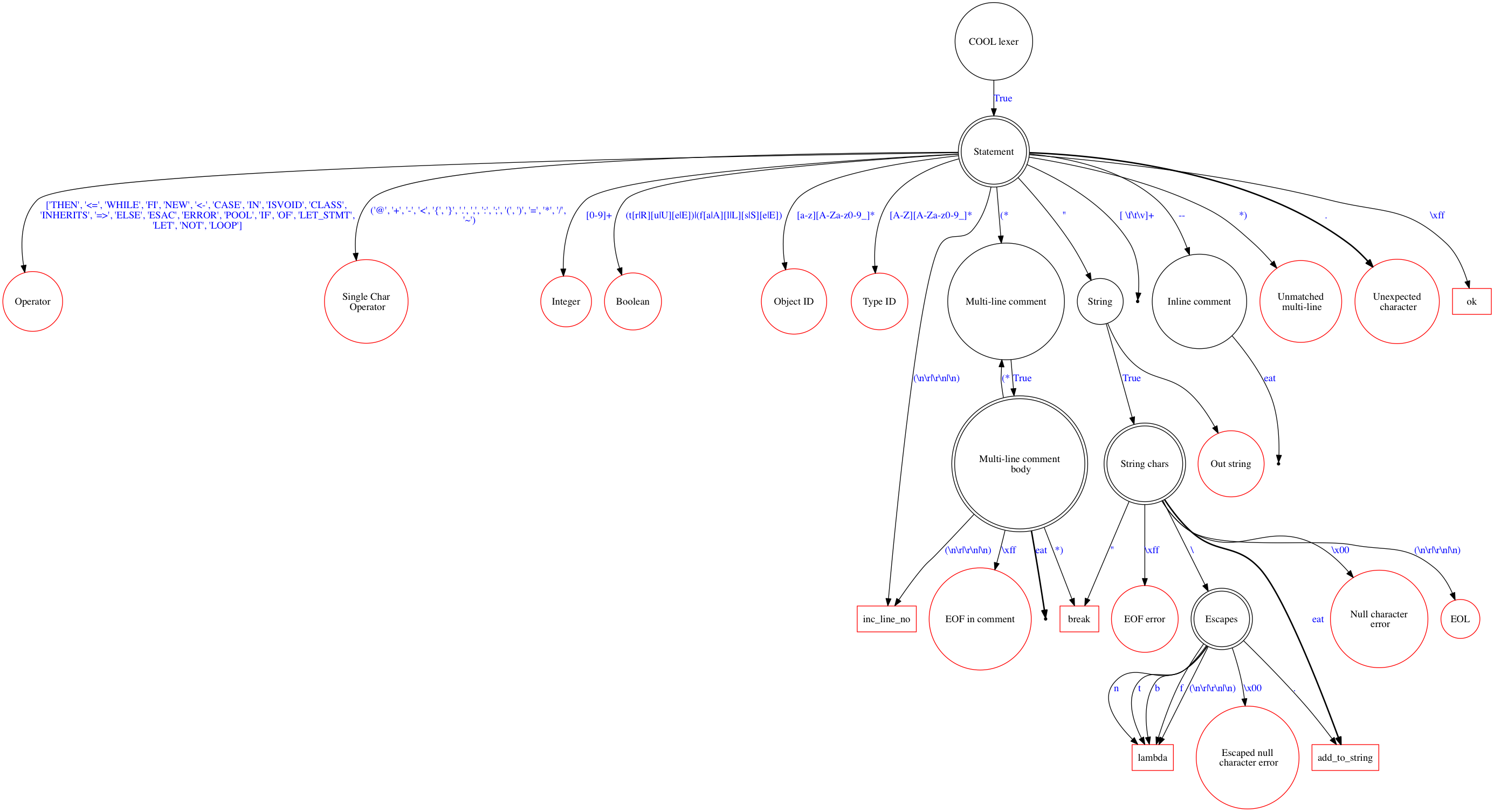

Here is an example of the COOL example graph picture:

DotExport is a child of ExportProcess class that overwrites export_* methods. It also adds DotExport.export_empty() method to export the relations with empty Relation.object.

The picture above was generated with the following code:

l = CoolLexer()

d = DotExport()

d(d.NEW, l.builder.graph, file='cool.gv')

The legend for the graph is:

- SelectiveNotion notions are double circles, other notions are ordinary circles.

- SelectiveNotion.default relations are marked as bold.

- Blue is the color of conditions.

- Red is the color of all actionable items (ActionNotion, ActionRelation, functions).

Performance Tips¶

There are two things that significantly influence the performance of Graph-talk. First is lookahead, which should not be used unnecessarily. It is better to break from infinite loops than to use flexible conditions.

Another factor that may slow the execution is the number of commands that the process supports. Note that the process is a participant of all dialogues; therefore, be careful with the number of handlers. It is not a good idea to use the ParsingProcess if there are no loops, selects or parsing relations.

If there is a need to extend the process class, make sure you assign the proper tag for the new handler, so that the condition will be checked only when needed. For example, ParsingProcess does not even consider the handler of “proceed” if the current message is not a dictionary. It saves a lot of time on unnecessary checks.

Python is a great language, but it is not very fast. Its syntax allows a very clean implementation of Graph-talk concepts, but porting it to faster platforms could bring a significant performance boost. You may contact the team if you are interested in such version.