User guide¶

The EM algorithm is an iterative method that estimates parameters for statistical models, where the model depends on unobserved latent variables. The EM iteration alternates between performing an expectation (E) step, which creates a function for the expectation of the log-likelihood evaluated using the current estimate for the parameters, and a maximization (M) step, which computes parameters maximizing the expected log-likelihood found on the E step. These parameter-estimates are then used to determine the distribution of the latent variables in the next E step [8].

Machines and trainers are the core components of Bob’s machine learning packages. Machines represent statistical models or other functions defined by parameters that can be learned by trainers or manually set. Below you will find machine/trainer guides for learning techniques available in this package.

K-Means¶

k-means [7] is a clustering method which aims to partition a set of

observations into

clusters with equal variance minimizing the following cost function

, where

is a given mean (also called centroid) and

is an observation.

This implementation has two stopping criteria. The first one is when the

maximum number of iterations is reached; the second one is when the difference

between of successive iterations are lower than a convergence

threshold.

In this implementation, the training consists in the definition of the

statistical model, called machine, (bob.learn.em.KMeansMachine) and

this statistical model is learned via a trainer

(bob.learn.em.KMeansTrainer).

Follow bellow an snippet on how to train a KMeans using Bob.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> data = numpy.array(

... [[3,-3,100],

... [4,-4,98],

... [3.5,-3.5,99],

... [-7,7,-100],

... [-5,5,-101]], dtype='float64')

>>> # Create a kmeans m with k=2 clusters with a dimensionality equal to 3

>>> kmeans_machine = bob.learn.em.KMeansMachine(2, 3)

>>> kmeans_trainer = bob.learn.em.KMeansTrainer()

>>> max_iterations = 200

>>> convergence_threshold = 1e-5

>>> # Train the KMeansMachine

>>> bob.learn.em.train(kmeans_trainer, kmeans_machine, data,

... max_iterations=max_iterations,

... convergence_threshold=convergence_threshold)

>>> print(kmeans_machine.means)

[[ -6. 6. -100.5]

[ 3.5 -3.5 99. ]]

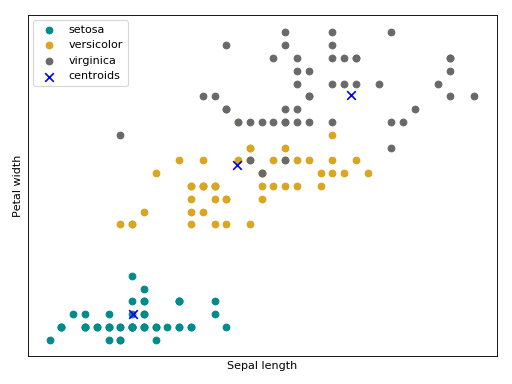

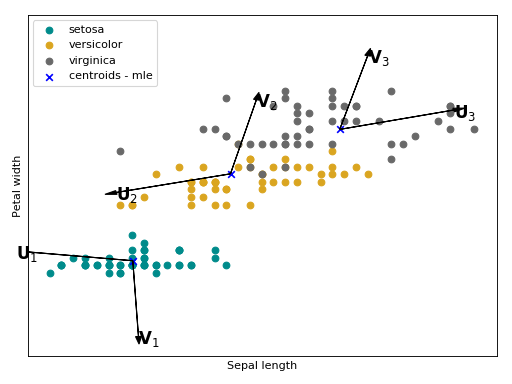

Bellow follow an intuition (source code + plot) of a kmeans training using the Iris flower dataset.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Gaussian mixture models¶

A Gaussian mixture model (GMM)

is a probabilistic model for density estimation. It assumes that all the data

points are generated from a mixture of a finite number of Gaussian

distributions. More formally, a GMM can be defined as:

, where

.

This statistical model is defined in the class

bob.learn.em.GMMMachine as bellow.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> # Create a GMM with k=2 Gaussians with the dimensionality of 3

>>> gmm_machine = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

There are plenty of ways to estimate ; the next subsections

explains some that are implemented in Bob.

Maximum likelihood Estimator (MLE)¶

In statistics, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is a method of estimating

the parameters of a statistical model given observations by finding the

that maximizes

for all

in your

dataset [10]. This optimization is done by the Expectation-Maximization

(EM) algorithm [8] and it is implemented by

bob.learn.em.ML_GMMTrainer.

A very nice explanation of EM algorithm for the maximum likelihood estimation can be found in this Mathematical Monk YouTube video.

Follow bellow an snippet on how to train a GMM using the maximum likelihood estimator.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> data = numpy.array(

... [[3,-3,100],

... [4,-4,98],

... [3.5,-3.5,99],

... [-7,7,-100],

... [-5,5,-101]], dtype='float64')

>>> # Create a kmeans model (machine) m with k=2 clusters

>>> # with a dimensionality equal to 3

>>> gmm_machine = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> # Using the MLE trainer to train the GMM:

>>> # True, True, True means update means/variances/weights at each

>>> # iteration

>>> gmm_trainer = bob.learn.em.ML_GMMTrainer(True, True, True)

>>> # Setting some means to start the training.

>>> # In practice, the output of kmeans is a good start for the MLE training

>>> gmm_machine.means = numpy.array(

... [[ -4., 2.3, -10.5],

... [ 2.5, -4.5, 59. ]])

>>> max_iterations = 200

>>> convergence_threshold = 1e-5

>>> # Training

>>> bob.learn.em.train(gmm_trainer, gmm_machine, data,

... max_iterations=max_iterations,

... convergence_threshold=convergence_threshold)

>>> print(gmm_machine.means)

[[ -6. 6. -100.5]

[ 3.5 -3.5 99. ]]

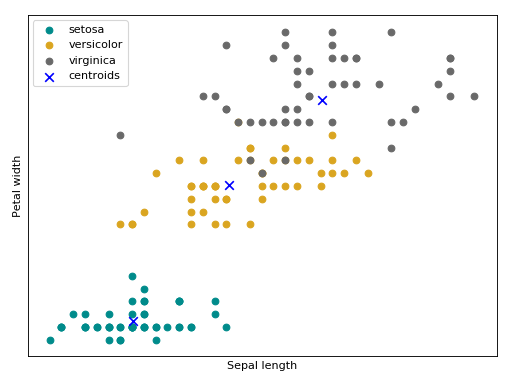

Bellow follow an intuition of the GMM trained the maximum likelihood estimator using the Iris flower dataset.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Maximum a posteriori Estimator (MAP)¶

Closely related to the MLE, Maximum a posteriori probability (MAP) is an

estimate that equals the mode of the posterior distribution by incorporating in

its loss function a prior distribution [11]. Commonly this prior distribution

(the values of ) is estimated with MLE. This optimization is done

by the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm [8] and it is implemented

by

bob.learn.em.MAP_GMMTrainer.

A compact way to write relevance MAP adaptation is by using GMM supervector

notation (this will be useful in the next subsections). The GMM supervector

notation consists of taking the parameters of (weights, means

and covariance matrices) of a GMM and create a single vector or matrix to

represent each of them. For each Gaussian component

, we can

represent the MAP adaptation as the following

, where

is our prior and

is the class offset.

Follow bellow an snippet on how to train a GMM using the MAP estimator.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> data = numpy.array(

... [[3,-3,100],

... [4,-4,98],

... [3.5,-3.5,99],

... [-7,7,-100],

... [-5,5,-101]], dtype='float64')

>>> # Creating a fake prior

>>> prior_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> # Set some random means for the example

>>> prior_gmm.means = numpy.array(

... [[ -4., 2.3, -10.5],

... [ 2.5, -4.5, 59. ]])

>>> # Creating the model for the adapted GMM

>>> adapted_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> # Creating the MAP trainer

>>> gmm_trainer = bob.learn.em.MAP_GMMTrainer(prior_gmm, relevance_factor=4)

>>>

>>> max_iterations = 200

>>> convergence_threshold = 1e-5

>>> # Training

>>> bob.learn.em.train(gmm_trainer, adapted_gmm, data,

... max_iterations=max_iterations,

... convergence_threshold=convergence_threshold)

>>> print(adapted_gmm.means)

[[ -4.667 3.533 -40.5 ]

[ 2.929 -4.071 76.143]]

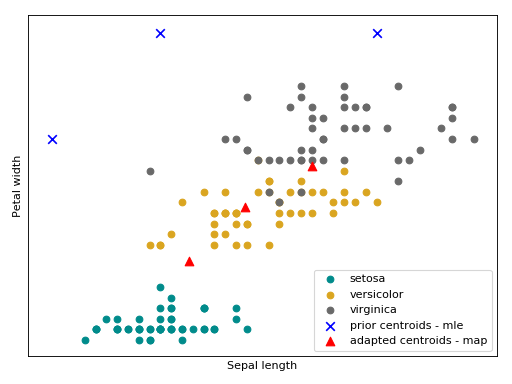

Bellow follow an intuition of the GMM trained with the MAP estimator using the Iris flower dataset.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Session Variability Modeling with Gaussian Mixture Models¶

In the aforementioned GMM based algorithms there is no explicit modeling of session variability. This section will introduce some session variability algorithms built on top of GMMs.

GMM statistics¶

Before introduce session variability for GMM based algorithms, we must

introduce a component called bob.learn.em.GMMStats. This component

is useful for some computation in the next sections.

bob.learn.em.GMMStats is a container that solves the Equations 8, 9

and 10 in [Reynolds2000] (also called, zeroth, first and second order GMM

statistics).

Given a GMM () and a set of samples

this component

accumulates statistics for each Gaussian component

.

Follow bellow a 1-1 relationship between statistics in [Reynolds2000] and the

properties in bob.learn.em.GMMStats:

- Eq (8) is

bob.learn.em.GMMStats.n:(also called responsibilities)

- Eq (9) is

bob.learn.em.GMMStats.sum_px:- Eq (10) is

bob.learn.em.GMMStats.sum_pxx:

where is the number of samples used to generate the stats.

The snippet bellow shows how to compute accumulated these statistics given a prior GMM.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> numpy.random.seed(10)

>>>

>>> data = numpy.array(

... [[0, 0.3, -0.2],

... [0.4, 0.1, 0.15],

... [-0.3, -0.1, 0],

... [1.2, 1.4, 1],

... [0.8, 1., 1]], dtype='float64')

>>> # Creating a fake prior with 2 Gaussians of dimension 3

>>> prior_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> prior_gmm.means = numpy.vstack((numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (1, 3)),

... numpy.random.normal(1, 0.5, (1, 3))))

>>> # All nice and round diagonal covariance

>>> prior_gmm.variances = numpy.ones((2, 3)) * 0.5

>>> prior_gmm.weights = numpy.array([0.3, 0.7])

>>> # Creating the container

>>> gmm_stats_container = bob.learn.em.GMMStats(2, 3)

>>> for d in data:

... prior_gmm.acc_statistics(d, gmm_stats_container)

>>>

>>> # Printing the responsibilities

>>> print(gmm_stats_container.n/gmm_stats_container.t)

[ 0.429 0.571]

Inter-Session Variability¶

Inter-Session Variability (ISV) modeling [3] [2] is a session variability modeling technique built on top of the Gaussian mixture modeling approach. It hypothesizes that within-class variations are embedded in a linear subspace in the GMM means subspace and these variations can be suppressed by an offset w.r.t each mean during the MAP adaptation.

In this generative model each sample is assumed to have been generated by a GMM

mean supervector with the following shape:

, where

is our prior,

is the session offset that we want to suppress and

is the class offset (with all session effects suppressed).

All possible sources of session variations is embedded in this matrix

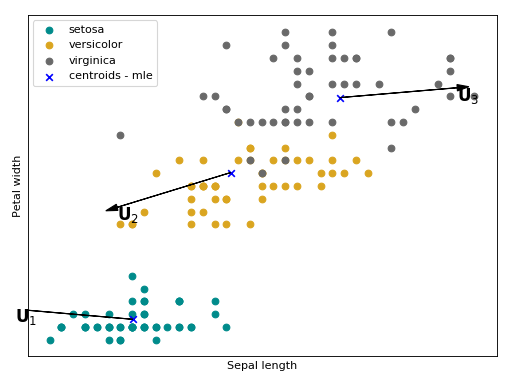

. Follow bellow an intuition of what is modeled with

in the

Iris flower dataset.

The arrows

,

and

are the directions of

the within class variations, with respect to each Gaussian component, that will

be suppressed a posteriori.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

The ISV statistical model is stored in this container

bob.learn.em.ISVBase and the training is performed by

bob.learn.em.ISVTrainer. The snippet bellow shows how to train a

Intersession variability modeling.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> numpy.random.seed(10)

>>>

>>> # Generating some fake data

>>> data_class1 = numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (10, 3))

>>> data_class2 = numpy.random.normal(-0.2, 0.2, (10, 3))

>>> data = [data_class1, data_class2]

>>> # Creating a fake prior with 2 gaussians of dimension 3

>>> prior_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> prior_gmm.means = numpy.vstack((numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (1, 3)),

... numpy.random.normal(1, 0.5, (1, 3))))

>>> # All nice and round diagonal covariance

>>> prior_gmm.variances = numpy.ones((2, 3)) * 0.5

>>> prior_gmm.weights = numpy.array([0.3, 0.7])

>>> # The input the the ISV Training is the statistics of the GMM

>>> gmm_stats_per_class = []

>>> for d in data:

... stats = []

... for i in d:

... gmm_stats_container = bob.learn.em.GMMStats(2, 3)

... prior_gmm.acc_statistics(i, gmm_stats_container)

... stats.append(gmm_stats_container)

... gmm_stats_per_class.append(stats)

>>> # Finally doing the ISV training

>>> subspace_dimension_of_u = 2

>>> relevance_factor = 4

>>> isvbase = bob.learn.em.ISVBase(prior_gmm, subspace_dimension_of_u)

>>> trainer = bob.learn.em.ISVTrainer(relevance_factor)

>>> bob.learn.em.train(trainer, isvbase, gmm_stats_per_class,

... max_iterations=50)

>>> # Printing the session offset w.r.t each Gaussian component

>>> print(isvbase.u)

[[-0.01 -0.027]

[-0.002 -0.004]

[ 0.028 0.074]

[ 0.012 0.03 ]

[ 0.033 0.085]

[ 0.046 0.12 ]]

Joint Factor Analysis¶

Joint Factor Analysis (JFA) [1] [2] is an extension of ISV. Besides the

within-class assumption (modeled with ), it also hypothesize that

between class variations are embedded in a low rank rectangular matrix

. In the supervector notation, this modeling has the following shape:

.

Follow bellow an intuition of what is modeled with and

in

the Iris flower

dataset. The arrows

,

and

are the directions of the

between class variations with respect to each Gaussian component that will be

added a posteriori.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

The JFA statistical model is stored in this container

bob.learn.em.JFABase and the training is performed by

bob.learn.em.JFATrainer. The snippet bellow shows how to train a

Intersession variability modeling.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> numpy.random.seed(10)

>>>

>>> # Generating some fake data

>>> data_class1 = numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (10, 3))

>>> data_class2 = numpy.random.normal(-0.2, 0.2, (10, 3))

>>> data = [data_class1, data_class2]

>>> # Creating a fake prior with 2 Gaussians of dimension 3

>>> prior_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> prior_gmm.means = numpy.vstack((numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (1, 3)),

... numpy.random.normal(1, 0.5, (1, 3))))

>>> # All nice and round diagonal covariance

>>> prior_gmm.variances = numpy.ones((2, 3)) * 0.5

>>> prior_gmm.weights = numpy.array([0.3, 0.7])

>>>

>>> # The input the the JFA Training is the statistics of the GMM

>>> gmm_stats_per_class = []

>>> for d in data:

... stats = []

... for i in d:

... gmm_stats_container = bob.learn.em.GMMStats(2, 3)

... prior_gmm.acc_statistics(i, gmm_stats_container)

... stats.append(gmm_stats_container)

... gmm_stats_per_class.append(stats)

>>>

>>> # Finally doing the JFA training

>>> subspace_dimension_of_u = 2

>>> subspace_dimension_of_v = 2

>>> relevance_factor = 4

>>> jfabase = bob.learn.em.JFABase(prior_gmm, subspace_dimension_of_u,

... subspace_dimension_of_v)

>>> trainer = bob.learn.em.JFATrainer()

>>> bob.learn.em.train_jfa(trainer, jfabase, gmm_stats_per_class,

... max_iterations=50)

>>> # Printing the session offset w.r.t each Gaussian component

>>> print(jfabase.v)

[[ 0.003 -0.006]

[ 0.041 -0.084]

[-0.261 0.53 ]

[-0.252 0.51 ]

[-0.387 0.785]

[-0.36 0.73 ]]

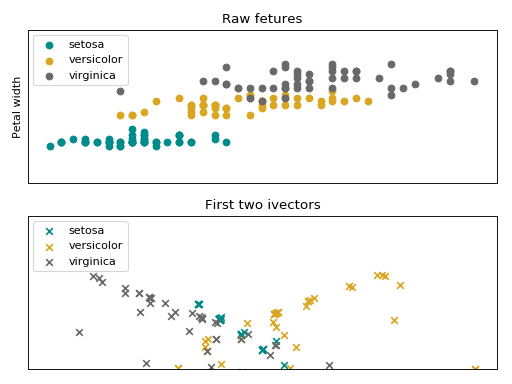

Total variability Modelling¶

Total Variability (TV) modeling [4] is a front-end initially introduced for

speaker recognition, which aims at describing samples by vectors of low

dimensionality called i-vectors. The model consists of a subspace

and a residual diagonal covariance matrix

, that are then used to

extract i-vectors, and is built upon the GMM approach. In the supervector

notation this modeling has the following shape:

.

Follow bellow an intuition of the data from the Iris flower dataset, embedded in the iVector space.

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

The iVector statistical model is stored in this container

bob.learn.em.IVectorMachine and the training is performed by

bob.learn.em.IVectorTrainer. The snippet bellow shows how to train

a Total variability modeling.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> numpy.random.seed(10)

>>>

>>> # Generating some fake data

>>> data_class1 = numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (10, 3))

>>> data_class2 = numpy.random.normal(-0.2, 0.2, (10, 3))

>>> data = [data_class1, data_class2]

>>>

>>> # Creating a fake prior with 2 gaussians of dimension 3

>>> prior_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(2, 3)

>>> prior_gmm.means = numpy.vstack((numpy.random.normal(0, 0.5, (1, 3)),

... numpy.random.normal(1, 0.5, (1, 3))))

>>> # All nice and round diagonal covariance

>>> prior_gmm.variances = numpy.ones((2, 3)) * 0.5

>>> prior_gmm.weights = numpy.array([0.3, 0.7])

>>>

>>> # The input the the TV Training is the statistics of the GMM

>>> gmm_stats_per_class = []

>>> for d in data:

... for i in d:

... gmm_stats_container = bob.learn.em.GMMStats(2, 3)

... prior_gmm.acc_statistics(i, gmm_stats_container)

... gmm_stats_per_class.append(gmm_stats_container)

>>>

>>> # Finally doing the TV training

>>> subspace_dimension_of_t = 2

>>>

>>> ivector_trainer = bob.learn.em.IVectorTrainer(update_sigma=True)

>>> ivector_machine = bob.learn.em.IVectorMachine(

... prior_gmm, subspace_dimension_of_t, 10e-5)

>>> # train IVector model

>>> bob.learn.em.train(ivector_trainer, ivector_machine,

... gmm_stats_per_class, 500)

>>>

>>> # Printing the session offset w.r.t each Gaussian component

>>> print(ivector_machine.t)

[[ 0.11 -0.203]

[-0.124 0.014]

[ 0.296 0.674]

[ 0.447 0.174]

[ 0.425 0.583]

[ 0.394 0.794]]

Linear Scoring¶

In MAP adaptation, ISV and JFA a traditional way to do scoring is via the log-likelihood ratio between the adapted model and the prior as the following:

(with varying for each approach).

A simplification proposed by [Glembek2009], called linear scoring, approximate this ratio using a first order Taylor series as the following:

where is the the GMM mean supervector (of the prior and the adapted

model),

is the variance, supervector,

is the first

order GMM statistics (

bob.learn.em.GMMStats.sum_px) and

, is possible channel offset (ISV).

This scoring technique is implemented in bob.learn.em.linear_scoring().

The snippet bellow shows how to compute scores using this approximation.

>>> import bob.learn.em

>>> import numpy

>>> # Defining a fake prior

>>> prior_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(3, 2)

>>> prior_gmm.means = numpy.array([[1, 1], [2, 2.1], [3, 3]])

>>> # Defining a fake prior

>>> adapted_gmm = bob.learn.em.GMMMachine(3,2)

>>> adapted_gmm.means = numpy.array([[1.5, 1.5], [2.5, 2.5], [2, 2]])

>>> # Defining an input

>>> input = numpy.array([[1.5, 1.5], [1.6, 1.6]])

>>> #Accumulating statistics of the GMM

>>> stats = bob.learn.em.GMMStats(3, 2)

>>> prior_gmm.acc_statistics(input, stats)

>>> score = bob.learn.em.linear_scoring(

... [adapted_gmm], prior_gmm, [stats], [],

... frame_length_normalisation=True)

>>> print(score)

[[ 0.254]]

Probabilistic Linear Discriminant Analysis (PLDA)¶

Probabilistic Linear Discriminant Analysis [16] is a probabilistic model that

incorporates components describing both between-class and within-class

variations. Given a mean , between-class and within-class subspaces

and

and residual noise

with zero mean and

diagonal covariance matrix

, the model assumes that a sample

is generated by the following process:

An Expectation-Maximization algorithm can be used to learn the parameters of

this model ,

and

. As these

parameters can be shared between classes, there is a specific container class

for this purpose, which is

bob.learn.em.PLDABase. The process is

described in detail in [17].

Let us consider a training set of two classes, each with 3 samples of dimensionality 3.

>>> data1 = numpy.array(

... [[3,-3,100],

... [4,-4,50],

... [40,-40,150]], dtype=numpy.float64)

>>> data2 = numpy.array(

... [[3,6,-50],

... [4,8,-100],

... [40,79,-800]], dtype=numpy.float64)

>>> data = [data1,data2]

Learning a PLDA model can be performed by instantiating the class

bob.learn.em.PLDATrainer, and calling the

bob.learn.em.train() method.

>>> # This creates a PLDABase container for input feature of dimensionality

>>> # 3 and with subspaces F and G of rank 1 and 2, respectively.

>>> pldabase = bob.learn.em.PLDABase(3,1,2)

>>> trainer = bob.learn.em.PLDATrainer()

>>> bob.learn.em.train(trainer, pldabase, data, max_iterations=10)

Once trained, this PLDA model can be used to compute the log-likelihood of a

set of samples given some hypothesis. For this purpose, a

bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine should be instantiated. Then, the

log-likelihood that a set of samples share the same latent identity variable

(i.e. the samples are coming from the same identity/class) is

obtained by calling the

bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine.compute_log_likelihood() method.

>>> plda = bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine(pldabase)

>>> samples = numpy.array(

... [[3.5,-3.4,102],

... [4.5,-4.3,56]], dtype=numpy.float64)

>>> loglike = plda.compute_log_likelihood(samples)

If separate models for different classes need to be enrolled, each of them with

a set of enrollment samples, then, several instances of

bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine need to be created and enrolled using

the bob.learn.em.PLDATrainer.enroll() method as follows.

>>> plda1 = bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine(pldabase)

>>> samples1 = numpy.array(

... [[3.5,-3.4,102],

... [4.5,-4.3,56]], dtype=numpy.float64)

>>> trainer.enroll(plda1, samples1)

>>> plda2 = bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine(pldabase)

>>> samples2 = numpy.array(

... [[3.5,7,-49],

... [4.5,8.9,-99]], dtype=numpy.float64)

>>> trainer.enroll(plda2, samples2)

Afterwards, the joint log-likelihood of the enrollment samples and of one or several test samples can be computed as previously described, and this separately for each model.

>>> sample = numpy.array([3.2,-3.3,58], dtype=numpy.float64)

>>> l1 = plda1.compute_log_likelihood(sample)

>>> l2 = plda2.compute_log_likelihood(sample)

In a verification scenario, there are two possible hypotheses:

and

share the same class.

and

are from different classes.

Using the methods bob.learn.em.PLDAMachine.log_likelihood_ratio() or

its alias __call__ function, the corresponding log-likelihood ratio will be

computed, which is defined in more formal way by:

>>> s1 = plda1(sample)

>>> s2 = plda2(sample)

Score Normalization¶

Score normalization aims to compensate statistical variations in output scores due to changes in the conditions across different enrollment and probe samples. This is achieved by scaling distributions of system output scores to better facilitate the application of a single, global threshold for authentication.

Bob has implemented 3 different strategies to normalize scores and these strategies are presented in the next subsections.

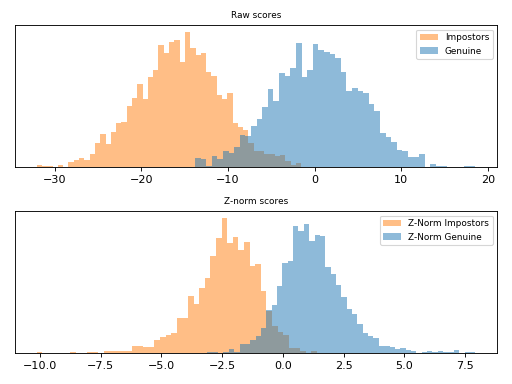

Z-Norm¶

Given a score , Z-Norm [Auckenthaler2000] and [Mariethoz2005]

(zero-normalization) scales this value by the mean (

) and standard

deviation (

) of an impostor score distribution. This score

distribution can be computed before hand and it is defined as the following.

This scoring technique is implemented in bob.learn.em.znorm(). Follow

bellow an example of score normalization using bob.learn.em.znorm().

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import bob.learn.em

import numpy

numpy.random.seed(10)

n_clients = 10

n_scores_per_client = 200

# Defining some fake scores for genuines and impostors

impostor_scores = numpy.random.normal(-15.5,

5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

genuine_scores = numpy.random.normal(0.5, 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

# Defining the scores for the statistics computation

z_scores = numpy.random.normal(-5., 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

# Z - Normalizing

z_norm_impostors = bob.learn.em.znorm(impostor_scores, z_scores)

z_norm_genuine = bob.learn.em.znorm(genuine_scores, z_scores)

# PLOTTING

figure = plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

ax = figure.axes

plt.title("Raw scores", fontsize=8)

plt.hist(impostor_scores.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Impostors', normed=True,

color='C1', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.hist(genuine_scores.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Genuine', normed=True,

color='C0', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.yticks([], [])

figure = plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

ax = figure.axes

plt.title("Z-norm scores", fontsize=8)

plt.hist(z_norm_impostors.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Z-Norm Impostors', normed=True,

color='C1', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.hist(z_norm_genuine.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Z-Norm Genuine', normed=True,

color='C0', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.yticks([], [])

plt.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Note

Observe how the scores were scaled in the plot above.

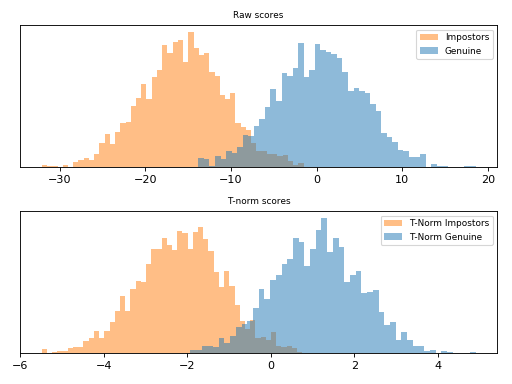

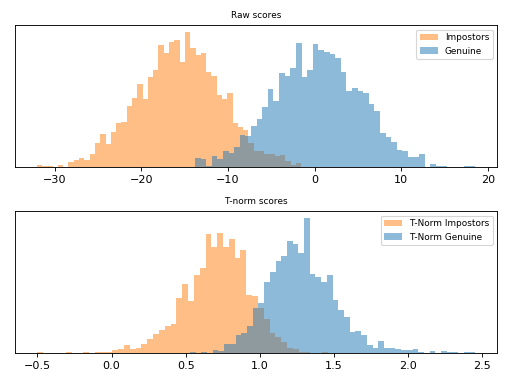

T-Norm¶

T-norm [Auckenthaler2000] and [Mariethoz2005] (Test-normalization) operates

in a probe-centric manner. If in the Z-Norm and

are

estimated using an impostor set of models and its scores, the t-norm computes

these statistics using the current probe sample against at set of models in a

co-hort

. A co-hort can be any semantic organization that is

sensible to your recognition task, such as sex (male and females), ethnicity,

age, etc and is defined as the following.

where, is

(the score given the claimed

model),

(

are the models of one co-hort) and

is the

standard deviation computed using the same criteria used to compute

.

This scoring technique is implemented in bob.learn.em.tnorm(). Follow

bellow an example of score normalization using bob.learn.em.tnorm().

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import bob.learn.em

import numpy

numpy.random.seed(10)

n_clients = 10

n_scores_per_client = 200

# Defining some fake scores for genuines and impostors

impostor_scores = numpy.random.normal(-15.5,

5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

genuine_scores = numpy.random.normal(0.5, 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

# Defining the scores for the statistics computation

t_scores = numpy.random.normal(-5., 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

# T - Normalizing

t_norm_impostors = bob.learn.em.tnorm(impostor_scores, t_scores)

t_norm_genuine = bob.learn.em.tnorm(genuine_scores, t_scores)

# PLOTTING

figure = plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

ax = figure.axes

plt.title("Raw scores", fontsize=8)

plt.hist(impostor_scores.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Impostors', normed=True,

color='C1', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.hist(genuine_scores.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Genuine', normed=True,

color='C0', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.yticks([], [])

figure = plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

ax = figure.axes

plt.title("T-norm scores", fontsize=8)

plt.hist(t_norm_impostors.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='T-Norm Impostors', normed=True,

color='C1', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.hist(t_norm_genuine.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='T-Norm Genuine', normed=True,

color='C0', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.yticks([], [])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Note

T-norm introduces extra computation during scoring, as the probe samples

need to be compared to each cohort model in order to have and

.

ZT-Norm¶

ZT-Norm [Auckenthaler2000] and [Mariethoz2005] consists in the application of

Z-Norm followed by a T-Norm and it is implemented

in bob.learn.em.ztnorm().

Follow bellow an example of score normalization using

bob.learn.em.ztnorm().

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import bob.learn.em

import numpy

numpy.random.seed(10)

n_clients = 10

n_scores_per_client = 200

# Defining some fake scores for genuines and impostors

impostor_scores = numpy.random.normal(-15.5,

5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

genuine_scores = numpy.random.normal(0.5, 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

# Defining the scores for the statistics computation

z_scores = numpy.random.normal(-5., 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

t_scores = numpy.random.normal(-6., 5, (n_scores_per_client, n_clients))

# T-normalizing the Z-scores

zt_scores = bob.learn.em.tnorm(z_scores, t_scores)

# ZT - Normalizing

zt_norm_impostors = bob.learn.em.ztnorm(

impostor_scores, z_scores, t_scores, zt_scores)

zt_norm_genuine = bob.learn.em.ztnorm(

genuine_scores, z_scores, t_scores, zt_scores)

# PLOTTING

figure = plt.subplot(2, 1, 1)

ax = figure.axes

plt.title("Raw scores", fontsize=8)

plt.hist(impostor_scores.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Impostors', normed=True,

color='C1', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.hist(genuine_scores.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='Genuine', normed=True,

color='C0', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.yticks([], [])

figure = plt.subplot(2, 1, 2)

ax = figure.axes

plt.title("T-norm scores", fontsize=8)

plt.hist(zt_norm_impostors.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='T-Norm Impostors', normed=True,

color='C1', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.hist(zt_norm_genuine.reshape(n_scores_per_client * n_clients),

label='T-Norm Genuine', normed=True,

color='C0', alpha=0.5, bins=50)

plt.legend(fontsize=8)

plt.yticks([], [])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

(Source code, png, hires.png, pdf)

Note

Observe how the scores were scaled in the plot above.

| [1] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2006.881693 |

| [2] | (1, 2) http://publications.idiap.ch/index.php/publications/show/2606 |

| [3] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2007.05.003 |

| [4] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2010.2064307 |

| [5] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2007.4409052 |

| [6] | http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2013.38 |

| [7] | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K-means_clustering |

| [8] | (1, 2, 3) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expectation-maximization_algorithm |

| [9] | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mixture_model |

| [10] | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximum_likelihood |

| [11] | http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximum_a_posteriori_estimation |

| [12] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2006.881693 |

| [13] | http://publications.idiap.ch/index.php/publications/show/2606 |

| [14] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.csl.2007.05.003 |

| [15] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TASL.2010.2064307 |

| [16] | http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2007.4409052 |

| [17] | http://doi.ieeecomputersociety.org/10.1109/TPAMI.2013.38 |