Contributing to Django¶

If you think working with Django is fun, wait until you start working on it. We’re passionate about helping Django users make the jump to contributing members of the community, so there are many ways you can help Django’s development:

- Blog about Django. We syndicate all the Django blogs we know about on the community page; contact jacob@jacobian.org if you’ve got a blog you’d like to see on that page.

- Report bugs and request features in our ticket tracker. Please read Reporting bugs, below, for the details on how we like our bug reports served up.

- Submit patches for new and/or fixed behavior. Please read Submitting patches, below, for details on how to submit a patch.

- Join the django-developers mailing list and share your ideas for how to improve Django. We’re always open to suggestions, although we’re likely to be skeptical of large-scale suggestions without some code to back it up.

- Triage patches that have been submitted by other users. Please read Ticket triage below, for details on the triage process.

That’s all you need to know if you’d like to join the Django development community. The rest of this document describes the details of how our community works and how it handles bugs, mailing lists, and all the other minutiae of Django development.

Reporting bugs¶

Well-written bug reports are incredibly helpful. However, there’s a certain amount of overhead involved in working with any bug tracking system, so your help in keeping our ticket tracker as useful as possible is appreciated. In particular:

- Do read the FAQ to see if your issue might be a well-known question.

- Do search the tracker to see if your issue has already been filed.

- Do ask on django-users first if you’re not sure if what you’re seeing is a bug.

- Do write complete, reproducible, specific bug reports. Include as much information as you possibly can, complete with code snippets, test cases, etc. This means including a clear, concise description of the problem, and a clear set of instructions for replicating the problem. A minimal example that illustrates the bug in a nice small test case is the best possible bug report.

- Don’t use the ticket system to ask support questions. Use the django-users list, or the #django IRC channel for that.

- Don’t use the ticket system to make large-scale feature requests. We like to discuss any big changes to Django’s core on the django-developers list before actually working on them.

- Don’t reopen issues that have been marked “wontfix”. This mark means that the decision has been made that we can’t or won’t fix this particular issue. If you’re not sure why, please ask on django-developers.

- Don’t use the ticket tracker for lengthy discussions, because they’re likely to get lost. If a particular ticket is controversial, please move discussion to django-developers.

- Don’t post to django-developers just to announce that you have filed a bug report. All the tickets are mailed to another list (django-updates), which is tracked by developers and triagers, so we see them as they are filed.

Reporting security issues¶

Report security issues to security@djangoproject.com. This is a private list only open to long-time, highly trusted Django developers, and its archives are not publicly readable.

In the event of a confirmed vulnerability in Django itself, we will take the following actions:

- Acknowledge to the reporter that we’ve received the report and that a fix is forthcoming. We’ll give a rough timeline and ask the reporter to keep the issue confidential until we announce it.

- Halt all other development as long as is needed to develop a fix, including patches against the current and two previous releases.

- Determine a go-public date for announcing the vulnerability and the fix. To try to mitigate a possible “arms race” between those applying the patch and those trying to exploit the hole, we will not announce security problems immediately.

- Pre-notify everyone we know to be running the affected version(s) of Django. We will send these notifications through private e-mail which will include documentation of the vulnerability, links to the relevant patch(es), and a request to keep the vulnerability confidential until the official go-public date.

- Publicly announce the vulnerability and the fix on the pre-determined go-public date. This will probably mean a new release of Django, but in some cases it may simply be patches against current releases.

Submitting patches¶

We’re always grateful for patches to Django’s code. Indeed, bug reports with associated patches will get fixed far more quickly than those without patches.

“Claiming” tickets¶

In an open-source project with hundreds of contributors around the world, it’s important to manage communication efficiently so that work doesn’t get duplicated and contributors can be as effective as possible. Hence, our policy is for contributors to “claim” tickets in order to let other developers know that a particular bug or feature is being worked on.

If you have identified a contribution you want to make and you’re capable of fixing it (as measured by your coding ability, knowledge of Django internals and time availability), claim it by following these steps:

- Create an account to use in our ticket system.

- If a ticket for this issue doesn’t exist yet, create one in our ticket tracker.

- If a ticket for this issue already exists, make sure nobody else has claimed it. To do this, look at the “Assigned to” section of the ticket. If it’s assigned to “nobody,” then it’s available to be claimed. Otherwise, somebody else is working on this ticket, and you either find another bug/feature to work on, or contact the developer working on the ticket to offer your help.

- Log into your account, if you haven’t already, by clicking “Login” in the upper right of the ticket page.

- Claim the ticket by clicking the radio button next to “Accept ticket” near the bottom of the page, then clicking “Submit changes.”

Ticket claimers’ responsibility¶

Once you’ve claimed a ticket, you have a responsibility to work on that ticket in a reasonably timely fashion. If you don’t have time to work on it, either unclaim it or don’t claim it in the first place!

Ticket triagers go through the list of claimed tickets from time to time, checking whether any progress has been made. If there’s no sign of progress on a particular claimed ticket for a week or two, a triager may ask you to relinquish the ticket claim so that it’s no longer monopolized and somebody else can claim it.

If you’ve claimed a ticket and it’s taking a long time (days or weeks) to code, keep everybody updated by posting comments on the ticket. If you don’t provide regular updates, and you don’t respond to a request for a progress report, your claim on the ticket may be revoked. As always, more communication is better than less communication!

Which tickets should be claimed?¶

Of course, going through the steps of claiming tickets is overkill in some cases. In the case of small changes, such as typos in the documentation or small bugs that will only take a few minutes to fix, you don’t need to jump through the hoops of claiming tickets. Just submit your patch and be done with it.

Patch style¶

Make sure your code matches our coding style.

Submit patches in the format returned by the svn diff command. An exception is for code changes that are described more clearly in plain English than in code. Indentation is the most common example; it’s hard to read patches when the only difference in code is that it’s indented.

Patches in git diff format are also acceptable.

When creating patches, always run svn diff from the top-level trunk directory – i.e., the one that contains django, docs, tests, AUTHORS, etc. This makes it easy for other people to apply your patches.

Attach patches to a ticket in the ticket tracker, using the “attach file” button. Please don’t put the patch in the ticket description or comment unless it’s a single line patch.

Name the patch file with a .diff extension; this will let the ticket tracker apply correct syntax highlighting, which is quite helpful.

Check the “Has patch” box on the ticket details. This will make it obvious that the ticket includes a patch, and it will add the ticket to the list of tickets with patches.

The code required to fix a problem or add a feature is an essential part of a patch, but it is not the only part. A good patch should also include a regression test to validate the behavior that has been fixed (and prevent the problem from arising again).

If the code associated with a patch adds a new feature, or modifies behavior of an existing feature, the patch should also contain documentation.

Non-trivial patches¶

A “non-trivial” patch is one that is more than a simple bug fix. It’s a patch that introduces Django functionality and makes some sort of design decision.

If you provide a non-trivial patch, include evidence that alternatives have been discussed on django-developers. If you’re not sure whether your patch should be considered non-trivial, just ask.

Ticket triage¶

Unfortunately, not all bug reports in the ticket tracker provide all the required details. A number of tickets have patches, but those patches don’t meet all the requirements of a good patch.

One way to help out is to triage bugs that have been reported by other users. A couple of dedicated volunteers work on this regularly, but more help is always appreciated.

Most of the workflow is based around the concept of a ticket’s “triage stage”. This stage describes where in its lifetime a given ticket is at any time. Along with a handful of flags, this field easily tells us what and who each ticket is waiting on.

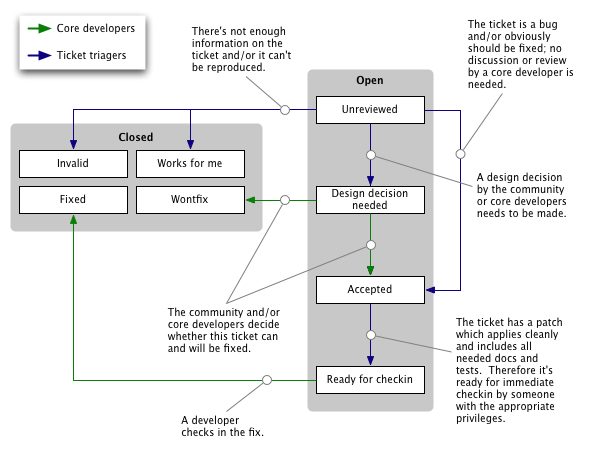

Since a picture is worth a thousand words, let’s start there:

We’ve got two official roles here:

- Core developers: people with commit access who make the big decisions and write the bulk of the code.

- Ticket triagers: trusted community members with a proven history of working with the Django community. As a result of this history, they have been entrusted by the core developers to make some of the smaller decisions about tickets.

Second, note the five triage stages:

- A ticket starts as “Unreviewed”, meaning that nobody has examined the ticket.

- “Design decision needed” means “this concept requires a design decision,” which should be discussed either in the ticket comments or on django-developers. The “Design decision needed” step will generally only be used for feature requests. It can also be used for issues that might be bugs, depending on opinion or interpretation. Obvious bugs (such as crashes, incorrect query results, or non-compliance with a standard) skip this step and move straight to “Accepted”.

- Once a ticket is ruled to be approved for fixing, it’s moved into the “Accepted” stage. This stage is where all the real work gets done.

- In some cases, a ticket might get moved to the “Someday/Maybe” state. This means the ticket is an enhancement request that we might consider adding to the framework if an excellent patch is submitted. These tickets are not a high priority.

- If a ticket has an associated patch (see below), a triager will review the patch. If the patch is complete, it’ll be marked as “ready for checkin” so that a core developer knows to review and check in the patches.

The second part of this workflow involves a set of flags the describe what the ticket has or needs in order to be “ready for checkin”:

- “Has patch”

- This means the ticket has an associated patch. These will be reviewed by the triage team to see if the patch is “good”.

- “Needs documentation”

- This flag is used for tickets with patches that need associated documentation. Complete documentation of features is a prerequisite before we can check a fix into the codebase.

- “Needs tests”

- This flags the patch as needing associated unit tests. Again, this is a required part of a valid patch.

- “Patch needs improvement”

- This flag means that although the ticket has a patch, it’s not quite ready for checkin. This could mean the patch no longer applies cleanly, or that the code doesn’t live up to our standards.

A ticket can be resolved in a number of ways:

- “fixed”

- Used by one of the core developers once a patch has been rolled into Django and the issue is fixed.

- “invalid”

- Used if the ticket is found to be incorrect. This means that the issue in the ticket is actually the result of a user error, or describes a problem with something other than Django, or isn’t a bug report or feature request at all (for example, some new users submit support queries as tickets).

- “wontfix”

- Used when a core developer decides that this request is not appropriate for consideration in Django. This is usually chosen after discussion in the django-developers mailing list, and you should feel free to join in when it’s something you care about.

- “duplicate”

- Used when another ticket covers the same issue. By closing duplicate tickets, we keep all the discussion in one place, which helps everyone.

- “worksforme”

- Used when the ticket doesn’t contain enough detail to replicate the original bug.

If you believe that the ticket was closed in error – because you’re still having the issue, or it’s popped up somewhere else, or the triagers have – made a mistake, please reopen the ticket and tell us why. Please do not reopen tickets that have been marked as “wontfix” by core developers.

Triage by the general community¶

Although the core developers and ticket triagers make the big decisions in the ticket triage process, there’s also a lot that general community members can do to help the triage process. In particular, you can help out by:

- Closing “Unreviewed” tickets as “invalid”, “worksforme” or “duplicate.”

- Promoting “Unreviewed” tickets to “Design decision needed” if a design decision needs to be made, or “Accepted” in case of obvious bugs.

- Correcting the “Needs tests”, “Needs documentation”, or “Has patch” flags for tickets where they are incorrectly set.

- Checking that old tickets are still valid. If a ticket hasn’t seen any activity in a long time, it’s possible that the problem has been fixed but the ticket hasn’t yet been closed.

- Contacting the owners of tickets that have been claimed but have not seen any recent activity. If the owner doesn’t respond after a week or so, remove the owner’s claim on the ticket.

- Identifying trends and themes in the tickets. If there a lot of bug reports about a particular part of Django, it may indicate we should consider refactoring that part of the code. If a trend is emerging, you should raise it for discussion (referencing the relevant tickets) on django-developers.

However, we do ask the following of all general community members working in the ticket database:

- Please don’t close tickets as “wontfix.” The core developers will make the final determination of the fate of a ticket, usually after consultation with the community.

- Please don’t promote tickets to “Ready for checkin” unless they are trivial changes – for example, spelling mistakes or broken links in documentation.

- Please don’t reverse a decision that has been made by a core developer. If you disagree with a discussion that has been made, please post a message to django-developers.

- Please be conservative in your actions. If you’re unsure if you should be making a change, don’t make the change – leave a comment with your concerns on the ticket, or post a message to django-developers.

Submitting and maintaining translations¶

Various parts of Django, such as the admin site and validation error messages, are internationalized. This means they display different text depending on a user’s language setting. For this, Django uses the same internationalization infrastructure available to Django applications described in the i18n documentation.

These translations are contributed by Django users worldwide. If you find an incorrect translation, or if you’d like to add a language that isn’t yet translated, here’s what to do:

Join the Django i18n mailing list and introduce yourself.

Make sure you read the notes about Specialties of Django translation.

Create translations using the methods described in the localization documentation. For this you will use the django-admin.py makemessages tool. In this particular case it should be run from the top-level django directory of the Django source tree.

The script runs over the entire Django source tree and pulls out all strings marked for translation. It creates (or updates) a message file in the directory conf/locale (for example for pt_BR, the file will be conf/locale/pt_BR/LC_MESSAGES/django.po).

Make sure that django-admin.py compilemessages -l <lang> runs without producing any warnings.

Repeat the last two steps for the djangojs domain (by appending the -d djangojs command line option to the django-admin.py invocations).

Optionally, review and update the conf/locale/<locale>/formats.py file to describe the date, time and numbers formatting particularities of your locale. See Format localization for details.

Create a diff against the current Subversion trunk.

Open a ticket in Django’s ticket system, set its Component field to Translations, and attach the patch to it.

Submitting javascript patches¶

Django’s admin system leverages the jQuery framework to increase the capabilities of the admin interface. In conjunction, there is an emphasis on admin javascript performance and minimizing overall admin media file size. Serving compressed or “minified” versions of javascript files is considered best practice in this regard.

To that end, patches for javascript files should include both the original code for future development (e.g. “foo.js”), and a compressed version for production use (e.g. “foo.min.js”). Any links to the file in the codebase should point to the compressed version.

To simplify the process of providing optimized javascript code, Django includes a handy script which should be used to create a “minified” version. This script is located at /contrib/admin/media/js/compress.py.

Behind the scenes, compress.py is a front-end for Google’s Closure Compiler which is written in Java. However, the Closure Compiler library is not bundled with Django directly, so those wishing to contribute complete javascript patches will need to download and install the library independently.

The Closure Compiler library requires Java version 6 or higher (Java 1.6 or higher on Mac OS X). Note that Mac OS X 10.5 and earlier did not ship with Java 1.6 by default, so it may be necessary to upgrade your Java installation before the tool will be functional. Also note that even after upgrading Java, the default /usr/bin/java command may remain linked to the previous Java binary, so relinking that command may be necessary as well.

Please don’t forget to run compress.py and include the diff of the minified scripts when submitting patches for Django’s javascript.

Django conventions¶

Various Django-specific code issues are detailed in this section.

Use of django.conf.settings¶

Modules should not in general use settings stored in django.conf.settings at the top level (i.e. evaluated when the module is imported). The explanation for this is as follows:

Manual configuration of settings (i.e. not relying on the DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE environment variable) is allowed and possible as follows:

from django.conf import settings

settings.configure({}, SOME_SETTING='foo')

However, if any setting is accessed before the settings.configure line, this will not work. (Internally, settings is a LazyObject which configures itself automatically when the settings are accessed if it has not already been configured).

So, if there is a module containing some code as follows:

from django.conf import settings

from django.core.urlresolvers import get_callable

default_foo_view = get_callable(settings.FOO_VIEW)

...then importing this module will cause the settings object to be configured. That means that the ability for third parties to import the module at the top level is incompatible with the ability to configure the settings object manually, or makes it very difficult in some circumstances.

Instead of the above code, a level of laziness or indirection must be used, such as django.utils.functional.LazyObject, django.utils.functional.lazy() or lambda.

Coding style¶

Please follow these coding standards when writing code for inclusion in Django:

Unless otherwise specified, follow PEP 8.

You could use a tool like pep8.py to check for some problems in this area, but remember that PEP 8 is only a guide, so respect the style of the surrounding code as a primary goal.

Use four spaces for indentation.

Use underscores, not camelCase, for variable, function and method names (i.e. poll.get_unique_voters(), not poll.getUniqueVoters).

Use InitialCaps for class names (or for factory functions that return classes).

Mark all strings for internationalization; see the i18n documentation for details.

In docstrings, use "action words" such as:

def foo(): """ Calculates something and returns the result. """ pass

Here's an example of what not to do:

def foo(): """ Calculate something and return the result. """ pass

Please don't put your name in the code you contribute. Our policy is to keep contributors' names in the AUTHORS file distributed with Django -- not scattered throughout the codebase itself. Feel free to include a change to the AUTHORS file in your patch if you make more than a single trivial change.

Template style¶

In Django template code, put one (and only one) space between the curly brackets and the tag contents.

Do this:

{{ foo }}

Don't do this:

{{foo}}

View style¶

In Django views, the first parameter in a view function should be called request.

Do this:

def my_view(request, foo): # ...Don't do this:

def my_view(req, foo): # ...

Model style¶

Field names should be all lowercase, using underscores instead of camelCase.

Do this:

class Person(models.Model): first_name = models.CharField(max_length=20) last_name = models.CharField(max_length=40)

Don't do this:

class Person(models.Model): FirstName = models.CharField(max_length=20) Last_Name = models.CharField(max_length=40)

The class Meta should appear after the fields are defined, with a single blank line separating the fields and the class definition.

Do this:

class Person(models.Model): first_name = models.CharField(max_length=20) last_name = models.CharField(max_length=40) class Meta: verbose_name_plural = 'people'

Don't do this:

class Person(models.Model): first_name = models.CharField(max_length=20) last_name = models.CharField(max_length=40) class Meta: verbose_name_plural = 'people'

Don't do this, either:

class Person(models.Model): class Meta: verbose_name_plural = 'people' first_name = models.CharField(max_length=20) last_name = models.CharField(max_length=40)

The order of model inner classes and standard methods should be as follows (noting that these are not all required):

- All database fields

- Custom manager attributes

- class Meta

- def __unicode__()

- def __str__()

- def save()

- def get_absolute_url()

- Any custom methods

If choices is defined for a given model field, define the choices as a tuple of tuples, with an all-uppercase name, either near the top of the model module or just above the model class. Example:

GENDER_CHOICES = ( ('M', 'Male'), ('F', 'Female'), )

Documentation style¶

We place a high importance on consistency and readability of documentation. (After all, Django was created in a journalism environment!)

How to document new features¶

We treat our documentation like we treat our code: we aim to improve it as often as possible. This section explains how writers can craft their documentation changes in the most useful and least error-prone ways.

Documentation changes come in two forms:

- General improvements -- Typo corrections, error fixes and better explanations through clearer writing and more examples.

- New features -- Documentation of features that have been added to the framework since the last release.

Our policy is:

All documentation of new features should be written in a way that clearly designates the features are only available in the Django development version. Assume documentation readers are using the latest release, not the development version.

Our preferred way for marking new features is by prefacing the features' documentation with: ".. versionadded:: X.Y", followed by an optional one line comment and a mandatory blank line.

General improvements, or other changes to the APIs that should be emphasized should use the ".. versionchanged:: X.Y" directive (with the same format as the versionadded mentioned above.

There's a full page of information about the Django documentation system that you should read prior to working on the documentation.

Guidelines for ReST files¶

These guidelines regulate the format of our ReST documentation:

- In section titles, capitalize only initial words and proper nouns.

- Wrap the documentation at 80 characters wide, unless a code example is significantly less readable when split over two lines, or for another good reason.

Commonly used terms¶

Here are some style guidelines on commonly used terms throughout the documentation:

- Django -- when referring to the framework, capitalize Django. It is lowercase only in Python code and in the djangoproject.com logo.

- e-mail -- it has a hyphen.

- MySQL

- PostgreSQL

- Python -- when referring to the language, capitalize Python.

- realize, customize, initialize, etc. -- use the American "ize" suffix, not "ise."

- SQLite

- subclass -- it's a single word without a hyphen, both as a verb ("subclass that model") and as a noun ("create a subclass").

- Web, World Wide Web, the Web -- note Web is always capitalized when referring to the World Wide Web.

- Web site -- use two words, with Web capitalized.

Django-specific terminology¶

- model -- it's not capitalized.

- template -- it's not capitalized.

- URLconf -- use three capitalized letters, with no space before "conf."

- view -- it's not capitalized.

Committing code¶

Please follow these guidelines when committing code to Django's Subversion repository:

For any medium-to-big changes, where "medium-to-big" is according to your judgment, please bring things up on the django-developers mailing list before making the change.

If you bring something up on django-developers and nobody responds, please don't take that to mean your idea is great and should be implemented immediately because nobody contested it. Django's lead developers don't have a lot of time to read mailing-list discussions immediately, so you may have to wait a couple of days before getting a response.

Write detailed commit messages in the past tense, not present tense.

- Good: "Fixed Unicode bug in RSS API."

- Bad: "Fixes Unicode bug in RSS API."

- Bad: "Fixing Unicode bug in RSS API."

For commits to a branch, prefix the commit message with the branch name. For example: "magic-removal: Added support for mind reading."

Limit commits to the most granular change that makes sense. This means, use frequent small commits rather than infrequent large commits. For example, if implementing feature X requires a small change to library Y, first commit the change to library Y, then commit feature X in a separate commit. This goes a long way in helping all core Django developers follow your changes.

Separate bug fixes from feature changes.

Bug fixes need to be added to the current bugfix branch (e.g. the 1.0.X branch) as well as the current trunk.

If your commit closes a ticket in the Django ticket tracker, begin your commit message with the text "Fixed #abc", where "abc" is the number of the ticket your commit fixes. Example: "Fixed #123 -- Added support for foo". We've rigged Subversion and Trac so that any commit message in that format will automatically close the referenced ticket and post a comment to it with the full commit message.

If your commit closes a ticket and is in a branch, use the branch name first, then the "Fixed #abc." For example: "magic-removal: Fixed #123 -- Added whizbang feature."

For the curious: We're using a Trac post-commit hook for this.

If your commit references a ticket in the Django ticket tracker but does not close the ticket, include the phrase "Refs #abc", where "abc" is the number of the ticket your commit references. We've rigged Subversion and Trac so that any commit message in that format will automatically post a comment to the appropriate ticket.

Unit tests¶

Django comes with a test suite of its own, in the tests directory of the Django tarball. It's our policy to make sure all tests pass at all times.

The tests cover:

- Models and the database API (tests/modeltests/).

- Everything else in core Django code (tests/regressiontests)

- Contrib apps (django/contrib/<contribapp>/tests, see below)

We appreciate any and all contributions to the test suite!

The Django tests all use the testing infrastructure that ships with Django for testing applications. See Testing Django applications for an explanation of how to write new tests.

Running the unit tests¶

To run the tests, cd to the tests/ directory and type:

./runtests.py --settings=path.to.django.settings

Yes, the unit tests need a settings module, but only for database connection info. Your DATABASES setting needs to define two databases:

- A default database. This database should use the backend that you want to use for primary testing

- A database with the alias other. The other database is used to establish that queries can be directed to different databases. As a result, this database can use any backend you want. It doesn't need to use the same backend as the default database (although it can use the same backend if you want to).

If you're using the SQLite database backend, you need to define ENGINE for both databases, plus a TEST_NAME for the other database. The following is a minimal settings file that can be used to test SQLite:

DATABASES = {

'default': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3'

},

'other': {

'ENGINE': 'django.db.backends.sqlite3',

'TEST_NAME': 'other_db'

}

}

As a convenience, this settings file is included in your Django distribution. It is called test_sqlite, and is included in the tests directory. This allows you to get started running the tests against the sqlite database without doing anything on your filesystem. However it should be noted that running against other database backends is recommended for certain types of test cases.

To run the tests with this included settings file, cd to the tests/ directory and type:

./runtests.py --settings=test_sqlite

If you're using another backend, you will need to provide other details for each database:

- The USER option for each of your databases needs to specify an existing user account for the database.

- The PASSWORD option needs to provide the password for the USER that has been specified.

- The NAME option must be the name of an existing database to which the given user has permission to connect. The unit tests will not touch this database; the test runner creates a new database whose name is NAME prefixed with test_, and this test database is deleted when the tests are finished. This means your user account needs permission to execute CREATE DATABASE.

You will also need to ensure that your database uses UTF-8 as the default character set. If your database server doesn't use UTF-8 as a default charset, you will need to include a value for TEST_CHARSET in the settings dictionary for the applicable database.

If you want to run the full suite of tests, you'll need to install a number of dependencies:

- PyYAML

- Markdown

- Textile

- Docutils

- setuptools

- memcached, plus the either the python-memcached or cmemcached Python binding

- gettext (gettext on Windows)

If you want to test the memcached cache backend, you will also need to define a CACHE_BACKEND setting that points at your memcached instance.

Each of these dependencies is optional. If you're missing any of them, the associated tests will be skipped.

To run a subset of the unit tests, append the names of the test modules to the runtests.py command line. See the list of directories in tests/modeltests and tests/regressiontests for module names.

As an example, if Django is not in your PYTHONPATH, you placed settings.py in the tests/ directory, and you'd like to only run tests for generic relations and internationalization, type:

PYTHONPATH=`pwd`/..

./runtests.py --settings=settings generic_relations i18n

Contrib apps¶

Tests for apps in django/contrib/ go in their respective directories under django/contrib/, in a tests.py file. (You can split the tests over multiple modules by using a tests directory in the normal Python way.)

For the tests to be found, a models.py file must exist (it doesn't have to have anything in it). If you have URLs that need to be mapped, put them in tests/urls.py.

To run tests for just one contrib app (e.g. markup), use the same method as above:

./runtests.py --settings=settings markup

Requesting features¶

We're always trying to make Django better, and your feature requests are a key part of that. Here are some tips on how to most effectively make a request:

- Request the feature on django-developers, not in the ticket tracker; it'll get read more closely if it's on the mailing list.

- Describe clearly and concisely what the missing feature is and how you'd like to see it implemented. Include example code (non-functional is OK) if possible.

- Explain why you'd like the feature. In some cases this is obvious, but since Django is designed to help real developers get real work done, you'll need to explain it, if it isn't obvious why the feature would be useful.

As with most open-source projects, code talks. If you are willing to write the code for the feature yourself or if (even better) you've already written it, it's much more likely to be accepted. If it's a large feature that might need multiple developers we're always happy to give you an experimental branch in our repository; see below.

Branch policy¶

In general, the trunk must be kept stable. People should be able to run production sites against the trunk at any time. Additionally, commits to trunk ought to be as atomic as possible -- smaller changes are better. Thus, large feature changes -- that is, changes too large to be encapsulated in a single patch, or changes that need multiple eyes on them -- must happen on dedicated branches.

This means that if you want to work on a large feature -- anything that would take more than a single patch, or requires large-scale refactoring -- you need to do it on a feature branch. Our development process recognizes two options for feature branches:

Feature branches using a distributed revision control system like Git, Mercurial, Bazaar, etc.

If you're familiar with one of these tools, this is probably your best option since it doesn't require any support or buy-in from the Django core developers.

However, do keep in mind that Django will continue to use Subversion for the foreseeable future, and this will naturally limit the recognition of your branch. Further, if your branch becomes eligible for merging to trunk you'll need to find a core developer familiar with your DVCS of choice who'll actually perform the merge.

If you do decided to start a distributed branch of Django and choose to make it public, please add the branch to the Django branches wiki page.

Feature branches using SVN have a higher bar. If you want a branch in SVN itself, you'll need a "mentor" among the core committers. This person is responsible for actually creating the branch, monitoring your process (see below), and ultimately merging the branch into trunk.

If you want a feature branch in SVN, you'll need to ask in django-developers for a mentor.

Branch rules¶

We've got a few rules for branches born out of experience with what makes a successful Django branch.

DVCS branches are obviously not under central control, so we have no way of enforcing these rules. However, if you're using a DVCS, following these rules will give you the best chance of having a successful branch (read: merged back to trunk).

Developers with branches in SVN, however, must follow these rules. The branch mentor will keep on eye on the branch and will delete it if these rules are broken.

Only branch entire copies of the Django tree, even if work is only happening on part of that tree. This makes it painless to switch to a branch.

Merge changes from trunk no less than once a week, and preferably every couple-three days.

In our experience, doing regular trunk merges is often the difference between a successful branch and one that fizzles and dies.

If you're working on an SVN branch, you should be using svnmerge.py to track merges from trunk.

Keep tests passing and documentation up-to-date. As with patches, we'll only merge a branch that comes with tests and documentation.

Once the branch is stable and ready to be merged into the trunk, alert django-developers.

After a branch has been merged, it should be considered "dead"; write access to it will be disabled, and old branches will be periodically "trimmed." To keep our SVN wrangling to a minimum, we won't be merging from a given branch into the trunk more than once.

Using branches¶

To use a branch, you'll need to do two things:

- Get the branch's code through Subversion.

- Point your Python site-packages directory at the branch's version of the django package rather than the version you already have installed.

Getting the code from Subversion¶

To get the latest version of a branch's code, check it out using Subversion:

svn co http://code.djangoproject.com/svn/django/branches/<branch>/

...where <branch> is the branch's name. See the list of branch names.

Alternatively, you can automatically convert an existing directory of the Django source code as long as you've checked it out via Subversion. To do the conversion, execute this command from within your django directory:

svn switch http://code.djangoproject.com/svn/django/branches/<branch>/

The advantage of using svn switch instead of svn co is that the switch command retains any changes you might have made to your local copy of the code. It attempts to merge those changes into the "switched" code. The disadvantage is that it may cause conflicts with your local changes if the "switched" code has altered the same lines of code.

(Note that if you use svn switch, you don't need to point Python at the new version, as explained in the next section.)

Pointing Python at the new Django version¶

Once you've retrieved the branch's code, you'll need to change your Python site-packages directory so that it points to the branch version of the django directory. (The site-packages directory is somewhere such as /usr/lib/python2.4/site-packages or /usr/local/lib/python2.4/site-packages or C:\Python\site-packages.)

The simplest way to do this is by renaming the old django directory to django.OLD and moving the trunk version of the code into the directory and calling it django.

Alternatively, you can use a symlink called django that points to the location of the branch's django package. If you want to switch back, just change the symlink to point to the old code.

A third option is to use a path file (<something>.pth) which should work on all systems (including Windows, which doesn't have symlinks available). First, make sure there are no files, directories or symlinks named django in your site-packages directory. Then create a text file named django.pth and save it to your site-packages directory. That file should contain a path to your copy of Django on a single line and optional comments. Here is an example that points to multiple branches. Just uncomment the line for the branch you want to use ('Trunk' in this example) and make sure all other lines are commented:

# Trunk is a svn checkout of:

# http://code.djangoproject.com/svn/django/trunk/

#

/path/to/trunk

# <branch> is a svn checkout of:

# http://code.djangoproject.com/svn/django/branches/<branch>/

#

#/path/to/<branch>

# On windows a path may look like this:

# C:/path/to/<branch>

If you're using Django 0.95 or earlier and installed it using python setup.py install, you'll have a directory called something like Django-0.95-py2.4.egg instead of django. In this case, edit the file setuptools.pth and remove the line that references the Django .egg file. Then copy the branch's version of the django directory into site-packages.

Deciding on features¶

Once a feature's been requested and discussed, eventually we'll have a decision about whether to include the feature or drop it.

Whenever possible, we strive for a rough consensus. To that end, we'll often have informal votes on django-developers about a feature. In these votes we follow the voting style invented by Apache and used on Python itself, where votes are given as +1, +0, -0, or -1. Roughly translated, these votes mean:

- +1: "I love the idea and I'm strongly committed to it."

- +0: "Sounds OK to me."

- -0: "I'm not thrilled, but I won't stand in the way."

- -1: "I strongly disagree and would be very unhappy to see the idea turn into reality."

Although these votes on django-developers are informal, they'll be taken very seriously. After a suitable voting period, if an obvious consensus arises we'll follow the votes.

However, consensus is not always possible. Tough decisions will be discussed by all full committers and finally decided by the Benevolent Dictators for Life, Adrian and Jacob.

Commit access¶

Django has two types of committers:

- Full committers

These are people who have a long history of contributions to Django's codebase, a solid track record of being polite and helpful on the mailing lists, and a proven desire to dedicate serious time to Django's development.

The bar is very high for full commit access. It will only be granted by unanimous approval of all existing full committers, and the decision will err on the side of rejection.

- Partial committers

These are people who are "domain experts." They have direct check-in access to the subsystems that fall under their jurisdiction, and they're given a formal vote in questions that involve their subsystems. This type of access is likely to be given to someone who contributes a large subframework to Django and wants to continue to maintain it.

Like full committers, partial commit access is by unanimous approval of all full committers (and any other partial committers in the same area). However, the bar is set lower; proven expertise in the area in question is likely to be sufficient.

To request commit access, please contact an existing committer privately. Public requests for commit access are potential flame-war starters, and will be ignored.

Last update:

Jul 05, 2010