Tutorial¶

Overview¶

Welcome to the circuits tutorial. This 5-minute tutorial will guide you through the basic concepts of circuits. The goal is to introduce new concepts incrementally with walk-through examples that you can try out! By the time you’ve finished, you should have a good basic understanding of circuits, how it feels and where to go from there.

The Component¶

First up, let’s show how you can use the Component and run it in a very simple application.

1 2 3 4 5 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component

Component().run()

|

Okay so that’s pretty boring as it doesn’t do very much! But that’s okay... Read on!

Let’s try to create our own custom Component called MyComponent. This is done using normal Python subclassing.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component

class MyComponent(Component):

"""My Component"""

MyComponent().run()

|

Okay, so this still isn’t very useful! But at least we can create custom components with the behavior we want.

Let’s move on to something more interesting...

Note

Component(s) in circuits are what sets circuits apart from other Asynchronous or Concurrent Application Frameworks. Components(s) are used as building blocks from simple behaviors to complex ones (composition of simpler components to form more complex ones).

Event Handlers¶

Let’s now extend our little example to say “Hello World!” when it’s started.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component

class MyComponent(Component):

def started(self, *args):

print("Hello World!")

MyComponent().run()

|

Here we’ve created a simple Event Handler that listens for the started Event.

Note

Methods defined in a custom subclassed Component are automatically turned into Event Handlers. The only exception to this are methods prefixed with an underscore (_).

Note

If you do not want this automatic behavior, inherit from BaseComponent instead which means you will have to use the ~circuits.core.handlers.handler decorator to define your Event Handlers.

Running this we get:

Hello World!

Alright! We have something slightly more useful! Whoohoo it says hello!

Note

Press ^C (CTRL + C) to exit.

Registering Components¶

So now that we’ve learned how to use a Component, create a custom Component and create simple Event Handlers, let’s try something a bit more complex by creating a complex component made up of two simpler ones.

Note

We call this Component Composition which is the very essence of the circuits Application Framework.

Let’s create two components:

- Bob

- Fred

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component

class Bob(Component):

def started(self, *args):

print("Hello I'm Bob!")

class Fred(Component):

def started(self, *args):

print("Hello I'm Fred!")

(Bob() + Fred()).run()

|

Notice the way we register the two components Bob and Fred together ? Don’t worry if this doesn’t make sense right now. Think of it as putting two components together and plugging them into a circuit board.

Running this example produces the following result:

Hello I'm Bob!

Hello I'm Fred!

Cool! We have two components that each do something and print a simple message on the screen!

Complex Components¶

Now, what if we wanted to create a Complex Component? Let’s say we wanted to create a new Component made up of two other smaller components?

We can do this by simply registering components to a Complex Component during initialization.

Note

This is also called Component Composition and avoids the classical Diamond problem of Multiple Inheritance. In circuits we do not use Multiple Inheritance to create Complex Components made up of two or more base classes of components, we instead compose them together via registration.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component

from circuits.tools import graph

class Pound(Component):

def __init__(self):

super(Pound, self).__init__()

self.bob = Bob().register(self)

self.fred = Fred().register(self)

def started(self, *args):

print(graph(self.root))

class Bob(Component):

def started(self, *args):

print("Hello I'm Bob!")

class Fred(Component):

def started(self, *args):

print("Hello I'm Fred!")

Pound().run()

|

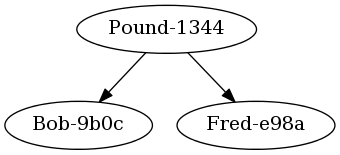

So now Pound is a Component that consists of two other components registered to it: Bob and Fred

The output of this is identical to the previous:

* <Pound/* 3391:MainThread (queued=0, channels=1, handlers=3) [R]>

* <Bob/* 3391:MainThread (queued=0, channels=1, handlers=1) [S]>

* <Fred/* 3391:MainThread (queued=0, channels=1, handlers=1) [S]>

Hello I'm Bob!

Hello I'm Fred!

The only difference is that Bob and Fred are now part of a more Complex Component called Pound. This can be illustrated by the following diagram:

Note

The extra lines in the above output are an ASCII representation of the above graph (produced by pydot + graphviz).

Cool :-)

Component Inheritance¶

Since circuits is a framework written for the Python Programming Language it naturally inherits properties of Object Orientated Programming (OOP) – such as inheritance.

So let’s take our Bob and Fred components and create a Base Component called Dog and modify our two dogs (Bob and Fred) to subclass this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component, Event

class woof(Event):

"""woof Event"""

class Pound(Component):

def __init__(self):

super(Pound, self).__init__()

self.bob = Bob().register(self)

self.fred = Fred().register(self)

def started(self, *args):

self.fire(woof())

class Dog(Component):

def woof(self):

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % self.name)

class Bob(Dog):

"""Bob"""

class Fred(Dog):

"""Fred"""

Pound().run()

|

Now let’s try to run this and see what happens:

Woof! I'm Bob!

Woof! I'm Fred!

So both dogs barked! Hmmm

Component Channels¶

What if we only want one of our dogs to bark? How do we do this without causing the other one to bark as well?

Easy! Use a separate channel like so:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component, Event

class woof(Event):

"""woof Event"""

class Pound(Component):

def __init__(self):

super(Pound, self).__init__()

self.bob = Bob().register(self)

self.fred = Fred().register(self)

def started(self, *args):

self.fire(woof(), self.bob)

class Dog(Component):

def woof(self):

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % self.name)

class Bob(Dog):

"""Bob"""

channel = "bob"

class Fred(Dog):

"""Fred"""

channel = "fred"

Pound().run()

|

Note

Events can be fired with either the .fire(...) or .fireEvent(...) method.

If you run this, you’ll get:

Woof! I'm Bob!

Event Objects¶

So far in our tutorial we have been defining an Event Handler for a builtin Event called started. What if we wanted to define our own Event Handlers and our own Events? You’ve already seen how easy it is to create a new Event Handler by simply defining a normal Python method on a Component.

Defining your own Events helps with documentation and testing and makes things a little easier.

Example:

class MyEvent(Event):

"""MyEvent"""

So here’s our example where we’ll define a new Event called Bark and make our Dog fire a Bark event when our application starts up.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component, Event

class bark(Event):

"""bark Event"""

class Pound(Component):

def __init__(self):

super(Pound, self).__init__()

self.bob = Bob().register(self)

self.fred = Fred().register(self)

class Dog(Component):

def started(self, *args):

self.fire(bark())

def bark(self):

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % self.name)

class Bob(Dog):

"""Bob"""

channel = "bob"

class Fred(Dog):

"""Fred"""

channel = "fred"

Pound().run()

|

If you run this, you’ll get:

Woof! I'm Bob!

Woof! I'm Fred!

The Debugger¶

Lastly...

Asynchronous programming has many advantages but can be a little harder to write and follow. A silently caught exception in an Event Handler, or an Event that never gets fired, or any number of other weird things can cause your application to fail and leave you scratching your head.

Fortunately circuits comes with a Debugger Component to help you keep track of what’s going on in your application, and allows you to tell what your application is doing.

Let’s say that we defined out bark Event Handler in our Dog Component as follows:

def bark(self):

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % name)

Now clearly there is no such variable as name in the local scope.

For reference here’s the entire example...

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 | #!/usr/bin/env python

from circuits import Component, Event

class bark(Event):

"""bark Event"""

class Pound(Component):

def __init__(self):

super(Pound, self).__init__()

self.bob = Bob().register(self)

self.fred = Fred().register(self)

class Dog(Component):

def started(self, *args):

self.fire(bark())

def bark(self):

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % name) # noqa

class Bob(Dog):

"""Bob"""

channel = "bob"

class Fred(Dog):

"""Fred"""

channel = "fred"

Pound().run()

|

If you run this, you’ll get:

That’s right! You get nothing! Why? Well in circuits any error or exception that occurs in a running application is automatically caught and dealt with in a way that lets your application “keep on going”. Crashing is unwanted behavior in a system so we expect to be able to recover from horrible situations.

SO what do we do? Well that’s easy. circuits comes with a Debugger that lets you log all events as well as all errors so you can quickly and easily discover which Event is causing a problem and which Event Handler to look at.

If you change Line 34 of our example...

From:

class Fred(Dog):

To:

from circuits import Debugger

(Pound() + Debugger()).run()

Then run this, you’ll get the following:

<Registered[bob:registered] [<Bob/bob 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=2, handlers=2) [S]>, <Pound/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=5, handlers=5) [R]>] {}>

<Registered[fred:registered] [<Fred/fred 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=2, handlers=2) [S]>, <Pound/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=5, handlers=5) [R]>] {}>

<Registered[*:registered] [<Debugger/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=1, handlers=1) [S]>, <Pound/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=5, handlers=5) [R]>] {}>

<Started[*:started] [<Pound/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=5, handlers=5) [R]>, None] {}>

<Bark[bob:bark] [] {}>

<Bark[fred:bark] [] {}>

<Error[*:exception] [<type 'exceptions.NameError'>, NameError("global name 'name' is not defined",), [' File "/home/prologic/work/circuits/circuits/core/manager.py", line 459, in __handleEvent\n retval = handler(*eargs, **ekwargs)\n', ' File "source/tutorial/009.py", line 22, in bark\n print("Woof! I\'m %s!" % name)\n'], <bound method ?.bark of <Bob/bob 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=2, handlers=2) [S]>>] {}>

ERROR <listener on ('bark',) {target='bob', priority=0.0}> (<type 'exceptions.NameError'>): global name 'name' is not defined

File "/home/prologic/work/circuits/circuits/core/manager.py", line 459, in __handleEvent

retval = handler(*eargs, **ekwargs)

File "source/tutorial/009.py", line 22, in bark

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % name)

<Error[*:exception] [<type 'exceptions.NameError'>, NameError("global name 'name' is not defined",), [' File "/home/prologic/work/circuits/circuits/core/manager.py", line 459, in __handleEvent\n retval = handler(*eargs, **ekwargs)\n', ' File "source/tutorial/009.py", line 22, in bark\n print("Woof! I\'m %s!" % name)\n'], <bound method ?.bark of <Fred/fred 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=2, handlers=2) [S]>>] {}>

ERROR <listener on ('bark',) {target='fred', priority=0.0}> (<type 'exceptions.NameError'>): global name 'name' is not defined

File "/home/prologic/work/circuits/circuits/core/manager.py", line 459, in __handleEvent

retval = handler(*eargs, **ekwargs)

File "source/tutorial/009.py", line 22, in bark

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % name)

^C<Signal[*:signal] [2, <frame object at 0x808e8ec>] {}>

<Stopped[*:stopped] [<Pound/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=5, handlers=5) [S]>] {}>

<Stopped[*:stopped] [<Pound/* 3191:MainThread (queued=0, channels=5, handlers=5) [S]>] {}>

You’ll notice whereas there was no output before there is now a pretty detailed output with the Debugger added to the application. Looking through the output, we find that the application does indeed start correctly, but when we fire our Bark Event it coughs up two exceptions, one for each of our dogs (Bob and Fred).

From the error we can tell where the error is and roughly where to look in the code.

Note

You’ll notice many other events that are displayed in the above output. These are all default events that circuits has builtin which your application can respond to. Each builtin Event has a special meaning with relation to the state of the application at that point.

See: circuits.core.events for detailed documentation regarding these events.

The correct code for the bark Event Handler should be:

def bark(self):

print("Woof! I'm %s!" % self.name)

Running again with our correction results in the expected output:

Woof! I'm Bob!

Woof! I'm Fred!

That’s it folks!

Hopefully this gives you a feel of what circuits is all about and an easy tutorial on some of the basic concepts. As you’re no doubt itching to get started on your next circuits project, here’s some recommended reading:

- ../faq

- ../api/index